The USA, China and Europe are busily tightening the subsidy screw for the semiconductor industry in order to secure added value and strategic positions for top chips.

A new race for chip factories and other semiconductor investments has broken out worldwide, hardly dampened by the recent, rather unfavorable balance sheet reports of several tech giants. Because what is at stake here is long-term value creation and high-tech jobs, but above all digital sovereignty, technological superiority in the key technology of microelectronics and global economic dominance. This new competition is being fought out with ever more dizzying subsidies, embargoes and verbal sabre-rattling. The main players in this semiconductor conflict are primarily the USA and China, while the major newcomers Taiwan and South Korea are discreetly trying to stay out of the firing line. Meanwhile, Europe is announcing ambitious goals, but is only active in selected niches in the global semiconductor world.

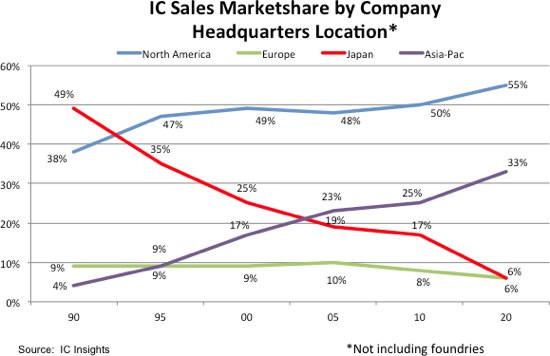

In the 1980s, Japan (red line) took the lead in the global semiconductor industry - and has dramatically lost market share since the prolonged recession of the 1990s. At the same time, however, it was not so much the Chinese who made gains, but primarily Taiwan, South Korea - and to some extent the USA (blue) itself, while the Europeans (green) continued to lose ground

In the 1980s, Japan (red line) took the lead in the global semiconductor industry - and has dramatically lost market share since the prolonged recession of the 1990s. At the same time, however, it was not so much the Chinese who made gains, but primarily Taiwan, South Korea - and to some extent the USA (blue) itself, while the Europeans (green) continued to lose ground

As the headlines in some media suggest that the USA and China are fighting a duel on equal terms, let's set the record straight: in terms of turnover, US companies continue to dominate the global semiconductor market with a 54% share, followed by South Korea with 22% and Taiwan with 9%. Japan, once a strong player in microelectronics, has slipped to a miserable 6%, as has Europe. Only behind them is China with just 4% [1].

So why all the fuss, you might ask? And why is an industry that has benefited so much from the international division of labor for decades as the semiconductor industry now the scene of neo-protectionism and global disputes?

Aftermath of the 2007 chip crisis

The conflict over jobs and value creation outsourced to Asia has been smouldering in the West for a long time and is affecting more and more sectors: First it was simple products such as hammers, then transportation ships and finally increasingly complex technology products that were no longer manufactured in Germany, England or the USA, but in Japan, Korea or China. This also applies to microelectronics, whose industrial focus had already shifted to Japan in the 1980s and then to Taiwan and South Korea in the new millennium.

The dispute began to escalate with the major chip crisis in 2007, to which the last major German memory chip company, Qimonda, also fell victim. Similar to the major demise of the German solar industry a little later, the public search for causes by Europeans and Americans focused on subsidies - some of which were only alleged - with which the Chinese, Koreans and Taiwanese were giving their chip and solar companies an unfair competitive advantage over their European and North American rivals. At the time, the Saxons in particular urged the German government and the EU to rescue Qimonda and prevent a further loss of semiconductor industry in Europe - at the time in vain.

"I want our chip production to double to around 20% of global production. I want Europe to produce more chips in Europe than the United States produces in its own country." Neelie Kroes, then Vice-President of the EU Commission, in 2013

In 2013, an attempt was made in Brussels to revive Europe's chip industry. EU Vice-President Neelie Kroes announced the goal of doubling the European share of global microelectronics production to 20%. The attempt remained half-hearted and fizzled out: instead of increasing, the European share has fallen to 6 to 7% to date. The 'Chips Act' announced by the EU in 2022 is now reviving the old targets with a new deadline, but is also considered underfunded.

China's chip production is still lagging behind technologically

Shortly after Nancy Pelosi's visit to Taiwan, US President Joe Biden demonstratively signs the 'CHIPS and Science Act' in front of the White House, which is intended to restore US microelectronics to its former greatnessThe situation is somewhatdifferent in the USA and China. The economic leaders in Beijing have been building up their own chip industry in small steps over decades. This has resulted in the emergence of very strong companies such as SMIC. This has enabled China to gradually expand its global market share, albeit still at a low level. However, Chinese chip manufacturers are still two to three generations behind the world leaders in terms of technology. In conjunction with the US sanctions policy, this is fueling fears in Beijing that the lack of availability of the latest circuits could severely slow down the otherwise quite successful Chinese industrial strategy. After all, decision-makers in Beijing as well as those in Berlin, Brussels and Washington have now realized that the global digital transformation also depends on access to the latest chips.

Shortly after Nancy Pelosi's visit to Taiwan, US President Joe Biden demonstratively signs the 'CHIPS and Science Act' in front of the White House, which is intended to restore US microelectronics to its former greatnessThe situation is somewhatdifferent in the USA and China. The economic leaders in Beijing have been building up their own chip industry in small steps over decades. This has resulted in the emergence of very strong companies such as SMIC. This has enabled China to gradually expand its global market share, albeit still at a low level. However, Chinese chip manufacturers are still two to three generations behind the world leaders in terms of technology. In conjunction with the US sanctions policy, this is fueling fears in Beijing that the lack of availability of the latest circuits could severely slow down the otherwise quite successful Chinese industrial strategy. After all, decision-makers in Beijing as well as those in Berlin, Brussels and Washington have now realized that the global digital transformation also depends on access to the latest chips.

This is why the West is now reacting much more sensitively than before to the Chinese People's Republic's mantra that Taiwan is just a renegade province. The fear is that if Beijing were to conquer the high-tech island, the West would lose enormously and China would gain enormously. The world's most modern chip factories of TSMC, UMC and other Taiwanese semiconductor giants could fall into the hands of the Chinese in one fell swoop, while entire supply chains of fabless companies in the USA and Europe would collapse without replacement. This is probably also why Nancy Pelosi (Democrat), Speaker of the US House of Representatives until January 2023, wanted to show Communist President Xi Jinping with her controversial visit to Taiwan in August 2022 that the US would not tolerate an invasion of Taiwan by China.

Donald Trump (Republican) had already initiated an economic policy turnaround in the United States. Under the much-quoted motto 'America First', he urged companies such as Apple and other tech corporations to bring more added value back to the USA. At the same time, Trump built an embargo wall against China. On the one hand, this was intended to protect and strengthen the US economy against China, which is a strong exporter, and on the other hand, it was intended to damage the business of non-American companies such as TSMC in Taiwan or ASML in the Netherlands, as they are no longer allowed to supply the Chinese with state-of-the-art chips or chip imagesetters.

Protectionist tendencies

Image: John Harrington / Public DomainDespitedifferences on other issues, Trump's successor Joe Biden (Democrat) has continued this protectionist and de-globalizing policy. His 'Chips Act' - which the EU has since followed with its own, lower-priced 'Chips Act' - is set to pump a total of around USD 280 billion into the US semiconductor industry. At the same time, the Biden administration is putting even more pressure on AMSL and other foreign manufacturers to stop selling modern equipment to SMIC & Co. Efforts to forge a US-led 'Chip 4 Alliance' between the United States, South Korea, Taiwan and Japan to cut off China from all semiconductor technology flows are also fueling the fire.

Image: John Harrington / Public DomainDespitedifferences on other issues, Trump's successor Joe Biden (Democrat) has continued this protectionist and de-globalizing policy. His 'Chips Act' - which the EU has since followed with its own, lower-priced 'Chips Act' - is set to pump a total of around USD 280 billion into the US semiconductor industry. At the same time, the Biden administration is putting even more pressure on AMSL and other foreign manufacturers to stop selling modern equipment to SMIC & Co. Efforts to forge a US-led 'Chip 4 Alliance' between the United States, South Korea, Taiwan and Japan to cut off China from all semiconductor technology flows are also fueling the fire.

Lost global economic claims have also contributed to this protectionist move by the US, which was originally so keen on free trade. One example among many: Intel, the former perennial leader, has now been overtaken by the South Koreans as the world's largest chip manufacturer and is also lagging somewhat behind Samsung and TSMC in terms of technology.

And finally, the global supply chain disruptions during the coronavirus pandemic showed both the USA and Europe what happens when China or Taiwan suddenly stop delivering. Under the slogans of 'resilience', 'digital sovereignty' and 'America First', all of this has fueled attempts in Europe and the USA to bring back once lost industries from Asia, setting in motion an unprecedented spiral of subsidies. Intel's commitment to locate in Magdeburg in return for billions in state subsidies is a good example of where this can lead: If, according to the old subsidy limits of the EU Commission, at most 15% of the $17 billion for these chip plants should have been injected, the German taxpayer now actually has to contribute 40%.

And the Taiwanese, who are reluctant to get involved in the major disputes between the world powers, suddenly see the need to invest in the West - a novelty for TSMC, which is otherwise completely focused on its home country. The world's largest chip contract manufacturer has already committed to a large chip factory in the USA and is also toying with the idea of building a mega-fab in Dresden. The subsidies announced, the supply chain experience of the coronavirus era and the security policy risks in the conflict between China, the USA and Taiwan are likely to play a role here.

References

[1] IC Insights 4/22