The European recycling market loses around one billion euros a year due to improperly declared scrap cars. The legal situation is clear. But the authorities are often misled or do not implement the regulations properly.

1 Introduction - Problem definition

The industry is responsible for implementing the End-of-Life Vehicle Ordinance in Germany. There are currently 5 car manufacturers, more than 1100 dismantling facilities, around 30 shredder facilities and individual post-shredder facilities that are responsible for the implementation of end-of-life vehicle collection, dismantling and recycling in Germany as "economic operators". In recent years, hundreds of millions have been invested in shredder and post-shredder technology in order to meet the constantly increasing requirements of environmental legislation. Examples include landfill legislation, the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance, immission control legislation and a number of other detailed regulations.

At the end of the 1990s, around 1.8 million vehicles were recycled in Germany every year. According to the Federal Motor Transport Authority, around 540,000 of the approximately 3.8 million decommissioned vehicles were recycled in Germany in 2006 and around 450,000 in 2014. The rest were exported as used cars, dismantled in Germany in unlicensed facilities or recycled as end-of-life vehicles in foreign facilities with much lower environmental standards.

Shredder operators speak of a sharp decline in the proportion of end-of-life vehicles in shredder input compared to a period before the End-of-Life Vehicle Ordinance, with the proportion being between 5% and 25%. Nevertheless, considerable bureaucratic effort is required to statistically record the quantities still remaining and recycled in Germany.

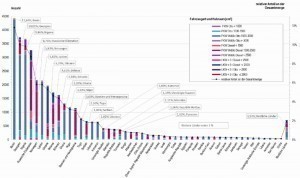

Preferred countries to which predominantly German vehicles are exported have now been published by the Federal Motor Transport Authority (KBA) and as part of a research project by the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) (see Figure 1). From the point of view of the recycling industry, the current statistics paint an alarming picture. On the one hand, the recycling rates in accordance with

Directive 2000/53/EC are being met, a number of undesirable developments can also be observed. For example, the UBA has been reporting for years that the whereabouts of hundreds of thousands of end-of-life vehicles are not statistically recorded, i.e. their whereabouts are unclear (1.2 million end-of-life vehicles in 2013, 1.38 million in 2012, 1.34 million in 2011, 1.29 million in 2010). In the meantime, it is assumed throughout the EU that over 3 million end-of-life vehicles are not recycled properly and harmlessly every year, instead leaving the EU market for Africa, Eastern Europe or Arab countries via various borders. This corresponds to a material value of around 1 billion euros per year, if one only conservatively assumes the scrap value, which means a considerable loss of raw materials for the European metal and steel industry. There are various reasons for the high proportion of exports. A lack of economic incentives for domestic recycling, a lack of enforcement of the statutory requirement to submit proof of recycling when finally deregistering an end-of-life vehicle, a lack of sanctions for failure to submit proof of recycling, numerous illegal storage sites and a lack of effective cross-border cooperation between the police and customs authorities. According to enforcement representatives, end-of-life vehicles that are to be exported are generally not in working order, are no longer safe to operate and the repair costs exceed the current market value. A fundamental problem is the difficult distinction between waste and used product. If the exported vehicle is still a used vehicle and is therefore not subject to waste legislation, it can be exported without a permit, but if it is already waste and still contains liquids, the planned export must be notified. This is examined in more detail below on the basis of the existing legal foundations from a European and national perspective. Figure 1: Main destination countries TOP 6 countries = 52 % of recorded exports, evaluation of customs statistics - destination countries vehicle classes M1 + N1 (source: Ökopol expert discussion on the fate of end-of-life vehicles)

Figure 1: Main destination countries TOP 6 countries = 52 % of recorded exports, evaluation of customs statistics - destination countries vehicle classes M1 + N1 (source: Ökopol expert discussion on the fate of end-of-life vehicles)

Directive 2000/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 September 2000 on end-of-life vehicles [1] is intended to ensure the appropriate management of around 8 to 9 million tons of end-of-life vehicles per year [2]. The directive is not based on the ideal of shredder treatment, but rather stipulates that reuse and recycling should be promoted and the use of toxic materials should be minimized during production. Although already outdated, the directive already pursues a remarkably modern approach to resource efficiency and resource conservation, "eco-design", the reconditioning of vehicle parts and their reuse, and thus largely meets the requirements of a modern circular economy.

2 The European legal situation

Against this background, it is particularly worrying and difficult to understand that people seem to have resigned themselves to the fact that millions of end-of-life vehicles worthy of disposal disappear from the scene every year and, to all appearances, reappear in regions in and around Europe where no appropriate disposal structures exist. This massively undermines the purpose of the directive and institutionalizes a significant implementation problem. A waste problem is often shifted by the fact that almost scrap-ready vehicles are sold to Eastern Europe, where they significantly pollute the air quality and become scrap after one or two years without being adequately disposed of. Corresponding effects are visible in Bosnia & Herzegovina, for example.

In the 2014 study on the "ex post evaluation" of the End-of-Life Vehicles Directive [3], it was already pointed out that a central problem of the Directive is that it does not contain its own definition of an end-of-life vehicle, but instead merely refers to the general definition of waste in Art. 3 No. 1 of the Waste Framework Directive [4], possibly a mistake in the birth of the Directive [5]. The general definition of waste is broad and contains the subjective element of the will to dispose. In this way, the waste status of an end-of-life vehicle can be interpreted flexibly. Unless there is an exceptional need for disposal, such as in the case of a burnt-out vehicle or a vehicle completely demolished as a result of a serious accident, it can always be argued that, in the absence of the will to dispose of the vehicle, it is not waste but a used vehicle worthy of repair. These circumstances are not helpful if a statistically clear distinction between a used vehicle and an end-of-life vehicle in the sense of waste is necessary.

The "Correspondent's Guidelines No 9 on shipment of waste vehicles" [6] should bring more clarity to this situation. However, these guidelines from 2011 are not legally binding and obviously did not have the desired effect of bringing more clarity to the actual distinction between end-of-life vehicles and used vehicles. There are currently discussions about revising these guidelines. Such a revision is planned in any case within 5 years of their adoption.

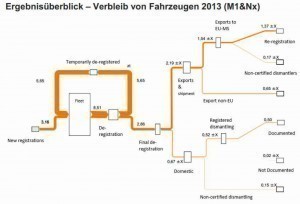

Some Member States, e.g. Austria, are attempting to clarify the distinction between end-of-life vehicles and used vehicles by means of a decree [7]. However, the approach chosen appears questionable. The decisive criterion for assessing the waste status of vehicles should be their reparability. This should be derived from the relationship between repair costs and current value. If the average restoration and repair costs in Austria that are required to restore a vehicle to a condition suitable for registration exceed the current value of the vehicle to a disproportionately high extent, the vehicle is waste. This sounds plausible at first, but is probably not readily compatible with Art. 34 TFEU [8], the prohibition of quantitative import restrictions and measures having equivalent effect, if the repairable vehicle is to be transported to a country where the repair costs are considerably lower.  Figure 2: Workshop transcript from the UBA research project "Whereabouts of end-of-life vehicles", showing the generation and whereabouts of end-of-life vehicles in million tons (source: Kummer records, 2016)An end-of-life vehicle that is disproportionately expensive to repair in Austria could perhaps be repaired in Romania at a price that would still be in reasonable relation to the existing utility value of the vehicle.

Figure 2: Workshop transcript from the UBA research project "Whereabouts of end-of-life vehicles", showing the generation and whereabouts of end-of-life vehicles in million tons (source: Kummer records, 2016)An end-of-life vehicle that is disproportionately expensive to repair in Austria could perhaps be repaired in Romania at a price that would still be in reasonable relation to the existing utility value of the vehicle.

value of the vehicle. This would be a desirable course from the point of view of a resource-conserving economy. A solution to the problem would therefore have to be sought at a different level. It would simply have to be more economical for the last owner to hand over a scrap vehicle to a recycler than to take it across the border in a questionable manner [9]. Anyone faced with the choice of giving away their non-repairable end-of-life vehicle or handing it over to an illegal exporter for 350 euros will often choose the latter route without asking many questions or even suspecting that they are doing something illegal.

In view of the 14 million end-of-life vehicles generated in the EU alone in 2010, it is obvious that we cannot rest on our laurels and that there is a need for action, particularly in the area of the whereabouts of the millions of end-of-life vehicles that disappear from the statistics every year. This is an urgent task, especially in view of the transformation of a linear economy into a circular economy.

End-of-life vehicles are not only raw materials that have to be recovered in a recycling process, they also contain a large number of parts that can be removed and reconditioned so that they can then be installed as spare parts with a full warranty [10]. There is considerable potential for the circular economy in this segment of vehicle parts processing, which serves the highest areas of the waste hierarchy, i.e. preparation for reuse. However, in order to make these parts available, the vehicles must ultimately remain in the country.

It would be perfectly conceivable and economically acceptable for manufacturers, dealers and buyers of passenger cars to create a system in which there are financial incentives to return a vehicle to a certified recycler at the end of its life cycle instead of letting it disappear into gray channels. It would be easy to imagine that the buyer pays a deposit when purchasing a new car, which is passed on via the intermediate owners to be paid back to the last owner of the vehicle at the end of its life cycle when it is returned. This may require a European clearing house to cover cases of intra-European cross-border sales.

The communication on the circular economy of 2.12.2015 [11] envisages greater efforts to combat the illegal shipment of end-of-life vehicles. A deposit system on motor vehicles would be an economic control instrument that promises to be more effective against illegal shipment than stricter controls and similar measures, which both cause higher overheads and promise a dubious effect. Deposit systems have already proven their worth for other products in various member states: Disposable packaging in Germany, electronic waste and batteries in Switzerland, etc.

The European Commission is currently investigating the causes and possible remedies for the statistical loss of end-of-life vehicles in a large-scale study. The results of this study are expected in 2017. However, Germany is conducting a similar study, the results of which should be available shortly. Initial results on whereabouts were presented at a public workshop (see chart 2). However, there is no indication as to which path might be taken in the future. However, it can be expected that a deposit solution would meet with fierce resistance from car manufacturers, as it would make sales visually more expensive and require a certain, albeit proportionate, administrative effort.

The Norwegian End-of-Life Vehicle Ordinance provides for a refund system for end-of-life vehicles registered after 1977 [12]. This regulation was deemed necessary in order to prevent end-of-life vehicles from being disposed of illegally in this sparsely populated country. At the very least, the question must be asked as to why this type of producer responsibility is not being adopted in the 28 EU Member States if it leads to end-of-life vehicles being recycled in Europe in a way that conserves resources.

3 The German national requirements

To answer the question of the distinction between used cars on the one hand and end-of-life vehicles on the other, the legal requirements in the Ordinance on the Transfer, Return and Environmentally Sound Disposal of End-of-Life Vehicles (Altfahrzeug-Verordnung-AltfahrzeugV) [13] must be taken into account.  Dismantled vehicle parts from scrap cars. They can be recycled or serve as used partsThisordinance was issued on the basis of the provisions on product responsibility (Sections 23 to 27 KrWG) provided for in the German Closed Substance Cycle Waste Management Act (KrWG) [14]. Product responsibility includes, in particular, the development, manufacture and marketing of products that are reusable, technically durable and, after use, suitable for proper, harmless and high-quality recovery and environmentally sound disposal in order to meet the objectives of the circular economy (Section 23 (2) no. 1 KrwG), the priority use of recyclable waste or secondary raw materials in the manufacture of products (Section 23 (2) no. 2 KrWG), the labeling of products containing harmful substances to ensure that the waste remaining after use is recycled or disposed of in an environmentally sound manner (§ 23 para. 2 no. 3 KrWG), the indication of return, reuse and recycling options or obligations and deposit regulations by labeling the products (§ 23 para. 2 no. 4 KrWG) as well as the take-back of the products and the waste remaining after use of the products and their subsequent environmentally sound recycling or disposal (§ 23 para. 2 no. 5 KrWG).

Dismantled vehicle parts from scrap cars. They can be recycled or serve as used partsThisordinance was issued on the basis of the provisions on product responsibility (Sections 23 to 27 KrWG) provided for in the German Closed Substance Cycle Waste Management Act (KrWG) [14]. Product responsibility includes, in particular, the development, manufacture and marketing of products that are reusable, technically durable and, after use, suitable for proper, harmless and high-quality recovery and environmentally sound disposal in order to meet the objectives of the circular economy (Section 23 (2) no. 1 KrwG), the priority use of recyclable waste or secondary raw materials in the manufacture of products (Section 23 (2) no. 2 KrWG), the labeling of products containing harmful substances to ensure that the waste remaining after use is recycled or disposed of in an environmentally sound manner (§ 23 para. 2 no. 3 KrWG), the indication of return, reuse and recycling options or obligations and deposit regulations by labeling the products (§ 23 para. 2 no. 4 KrWG) as well as the take-back of the products and the waste remaining after use of the products and their subsequent environmentally sound recycling or disposal (§ 23 para. 2 no. 5 KrWG).

3.1 Product responsibility system in accordance with the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance

This system of product responsibility for end-of-life vehicles essentially addresses the take-back obligations of vehicle manufacturers and the structure of these take-back obligations. These take-back obligations of the manufacturers apply to all end-of-life vehicles of their brand from the last holder or the public waste management authority in cases in which the holder or owner of the motor vehicle could not be identified (Section 3 (2) of the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance).3 In order to clarify the existence of take-back obligations in a specific individual case, it is important that the vehicle to be taken back is an end-of-life vehicle within the meaning of the statutory provisions. According to the definition in the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance, this means that it is a vehicle that is waste in accordance with Section 3 (1) KrWG. This means that the criteria that apply to waste in general are used to legally qualify a vehicle as an "end-of-life vehicle" within the meaning of the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance. In this respect, according to Section 3 (1) KrWG, it is important that the owner of the vehicle disposes of it, wants to dispose of it or must dispose of it. Accordingly, a "disposal" within the meaning of Section 3 (1) KrWG is to be assumed if the owner, with reference to the definition in Section 2 (1) No. 2 of the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance, sends the vehicle for recovery, which, according to Section 3 (2) KrWG, includes the processes listed in Annex 2 under R1 to R13. In the case of conventional vehicles that are currently subject to disposal as end-of-life vehicles, the focus will be on recycling and the recovery of metals and metal compounds (R4 in Annex 2 to the KrWG).3 (3) KrWG with regard to the definition in Section 2 (1) No. 2 AltfahrzeugV, the intention to dispose of is to be assumed with regard to those vehicles whose original purpose ceases to apply or is abandoned without a new purpose directly replacing it (Section 3 (3) No. 2 KrWG). This is likely to apply to vehicles that are handed over to recognized take-back facilities or to recognized dismantling facilities designated by a manufacturer for this purpose. Finally, the conditions under which a compulsory disposal can be assumed are defined in Section 3 (4) KrWG. According to this, the owner must dispose of a vehicle in accordance with the definition in Section 2 (1) No. 2 of the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance if it can no longer be used for its original purpose, is likely to endanger the public good, in particular the environment, now or in the future due to its specific condition, and its potential hazard can only be eliminated by proper and safe recovery or disposal in accordance with the statutory provisions or the ordinance issued on the basis of this Act. The requirements under the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance for the disposal of end-of-life vehicles, i.e. waste vehicles, have been established for this very purpose. According to the definition in Section 2 (1) No. 21 of the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance, the last holder registered in the vehicle registration document to whom the vehicle is or was registered is the last holder. The parties involved in these take-back obligations also include the public waste disposal authorities. Accordingly, the existing obligations under Section 20 (1) KrWG also apply to motor vehicles or trailers without valid registration plates if they are parked in public areas or outside built-up areas, if there are no indications of their theft or intended use and if they have not been removed within one month of a clearly visible request to do so being affixed to the vehicle.

-continued-

Note:

The views expressed here are the personal opinions of the authors and do not represent the views of the European Commission

The authors

Prof. Dr.-Ing. Wolfgang Klett, Köhler & Klett Partnerschaft von Rechtsanwälten mbB, CologneDr. Dipl.-Chem.

Beate Kummer, Kummer: Umweltkommunikation GmbH, Bonn/Rheinbreitbach, www.beatekummer.de

Prof. Dr. jur. Helmut Maurer, DG Environment, EU Commission, Brussels

Literature

[1] OJ L 269, 21.10.2000, P. 34

[2] On the quantities mentioned: BIOIS (2014), ex post evaluation of certain waste stream Directives, page 107

[3] Ex-post Evaluation of Five Waste Stream Directives, SWD (2014) 209 final of 2.7.2014

[4] OJ L 312, 22.11.2008, P. 3

[5] In this sense Christa Friedl, Ulrich Leuning (BDSV), Recycling Magazin 08/2012, p. 35.

[6] http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/shipments/guidance.htm

[7] Decree on the End-of-Life Vehicles Ordinance, April 2015, http://www.autopreisspiegel.at/docs/Erlass_zur_AltfahrzeugeVO.pdf

[8] Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, 2008/C 115/01

[9] A vivid and probably also completely accurate description of the background can be found in this article in "Die Presse" from 27.9.2015: http://diepresse.com/home/panorama/oesterreich/4830109/Diefinsteren-Wege-der-Schrottautos

[10] ACATECH workshop 13.10.2016 Berlin: http://www.acatech.de/de/ueber-uns/geschichte.html

[11] COM (2015) 614 final, closing the loop-An EU action plan for the Circular Economy, p. 10

[12] http://www.miljodirektoratet.no/no/Regelverk/Forskrifter/Regulations-relating-to-the-recycling-of-waste-Waste-Regulations/Chapter-4-End-of-life-vehicles/;https://books.google.be/books?id=7PiEN0C3K8EC&pg=PA145&lpg=PA145&dq=norway+end+of+life+vehicles&source=bl&ots=xE9Za1IUyQ&sig=00_fWcLYvzZ2EBhOTi3t1toeRTU&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiVsuHytJnQAhWIAcAKHagMAdwQ6AEIRDAK#v=onepage&q=norway%20end%20of%20life%20vehicles&f=false

[13] In the version published on June 21, 2002, BGBl. I, p. 2214.

[14] In the version of February 24, 2012, BGB l. I p. 212, last amended by art. 1a First Act amending the Batteries Act and the Closed Substance Cycle Waste Management Act of 20. 11 2015, BGBl. I p. 2071.