Developments over the past three years have shown that our globalized system of closely interlinked supply relationships is highly susceptible to disruption. These experiences show that the cost efficiency of supply chains can no longer be the sole criterion for entrepreneurial action or economic policy strategies. The legal regulation of supply chains is also facing some changes: On January 1, 2023, the German 'Act on Corporate Due Diligence in Supply Chains' (in short: Supply Chain Act) came into force. Such a law is also being negotiated at EU level. The strategic realignment should consider sustainability as a central component of resilience.

Developments over the past three years have shown that our globalized system of closely interlinked supply relationships entails considerable vulnerabilities to disruption. These experiences show that cost efficiency of supply chains can no longer be the sole criterion for entrepreneurial action or economic policy strategies. Some changes are also in store for the legal regulation of supply chains: On January 1, 2023, the German 'Act on Corporate Due Diligence in Supply Chains' (Supply Chain Act) came into force. Such a law is also being negotiated at EU level. The strategic realignment should consider sustainability as a central building block of resilience.

1 Introduction

Purified polycrystalline siliconInterruptionsin the supply of essential goods in the wake of the Covid19 pandemic have triggered an intense debate about transnational supply relationships. Since the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, the discussion has also focused on geopolitical tensions and dependencies on individual (insecure) partners as an additional risk factor - not only with regard to Russia, but also China in particular. As a result, the European Commission has set itself the goal of reducing excessive dependencies on trading partners in order to strengthen the resilience of European industry. The German government has also formulated industrial policy measures with a similar objective.

Purified polycrystalline siliconInterruptionsin the supply of essential goods in the wake of the Covid19 pandemic have triggered an intense debate about transnational supply relationships. Since the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, the discussion has also focused on geopolitical tensions and dependencies on individual (insecure) partners as an additional risk factor - not only with regard to Russia, but also China in particular. As a result, the European Commission has set itself the goal of reducing excessive dependencies on trading partners in order to strengthen the resilience of European industry. The German government has also formulated industrial policy measures with a similar objective.

This reorientation is particularly evident in strategically important sectors, such as the supply of mineral raw materials or the production of semiconductors. In order to strengthen the resilience of supply chains, risks - particularly in the form of geopolitical dynamics and critical dependencies, but also in the area of human rights and environmental risks - should be incorporated more strongly into entrepreneurial action and industrial policy planning and diversification opportunities should be developed.

The basic prerequisite for this is an in-depth analysis of the entire supply chain, from the extraction of raw materials to the end product. This must also take greater account of the social and environmental sustainability of supply chains. After all, resilience and sustainability of supply chains are not opposites; rather, they must be understood as complementary strategies.

2 Dependencies and vulnerability in transnational supply chains

The susceptibility of global supply chains to disruption is by no means a phenomenon of current times of crisis, but rather a side effect of increasingly complex and globalized supply chain systems. These are characterized by a combination of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity [1].

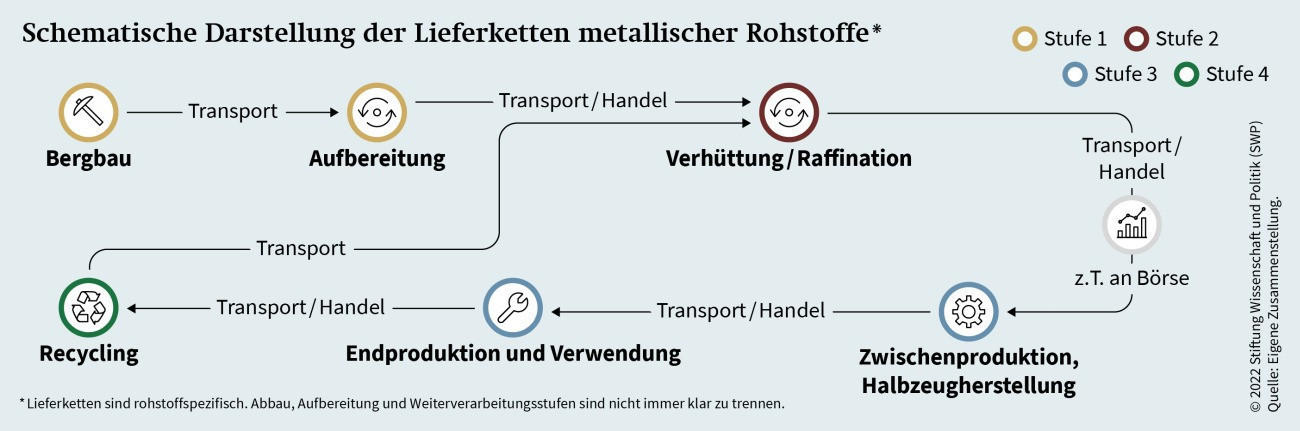

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of the stages of metal supply chains

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of the stages of metal supply chains

This can be illustrated well using mineral raw materials - the basis of industrial value creation. The supply chains of mineral raw materials can be represented schematically using four stages (see Fig. 1): the extraction of raw materials, refining production (i.e. the refinement of raw materials), further processing into intermediate products and the manufacture of end products, as well as recycling [2].

There are different dependencies and risks at all of these stages. German and European companies are primarily involved in final processing and therefore often have little knowledge of the risks in the upstream supply chain. According to the German Raw Materials Agency (DERA), however, there are high price and supply risks in precisely these areas. In addition, dependence on China is particularly pronounced here. The supply of refined products is particularly critical: 70% of these products have a high procurement risk; around 93% of production takes place in China [3].

Laboratory studies on microcircuits and the production of semiconductor wafersMineralraw materials are key elements for the production of semiconductors - their supply chain is therefore upstream. Some raw materials, such as silicon, are particularly critical. According to DERA, refined silicon, the basic raw material for the production of semiconductors, is subject to the group with the highest price and supply risks. Although deposits are available worldwide, mining is heavily concentrated in China: in 2021, China accounted for around 67% of global silicon production. The country is also by far the world's largest exporter of high-purity silicon [4]. This means that there are high risks to the secure supply of raw materials that are important for semiconductor production.

Laboratory studies on microcircuits and the production of semiconductor wafersMineralraw materials are key elements for the production of semiconductors - their supply chain is therefore upstream. Some raw materials, such as silicon, are particularly critical. According to DERA, refined silicon, the basic raw material for the production of semiconductors, is subject to the group with the highest price and supply risks. Although deposits are available worldwide, mining is heavily concentrated in China: in 2021, China accounted for around 67% of global silicon production. The country is also by far the world's largest exporter of high-purity silicon [4]. This means that there are high risks to the secure supply of raw materials that are important for semiconductor production.

In addition, the supply chain for semiconductors to the EU is itself characterized by major dependencies. It is concentrated to a relevant extent in Asia, with Taiwan accounting for around 64% of global production [5]. Two of the three largest contract manufacturers in the world, TSMC (53% market share alone) and UM, are based in Taiwan [6]. In turn, the EU is heavily dependent on US companies for development and design, as well as for the manufacture of devices and equipment for production.

Disruptions at one stage in these supply chains can have high multiplier effects. European companies are often dependent on individual suppliers and/or production countries; in the event of disruptions, there is little or no alternative to other suppliers. The reasons for potential disruptions along the supply chain are manifold. They range from country-specific risks such as strikes and protests to environmental and location-related risks, geopolitical dynamics and technological uncertainties, for example in the form of cyberattacks [7]. In addition, domestic and foreign policy developments can repeatedly lead to short-term production stoppages or even export stops, such as in 2021, when the People's Republic of China decided to temporarily halt magnesium exports, thus briefly interrupting global supplies.

With regard to semiconductor production, China's threats regarding a possible annexation of Taiwan also pose a potential risk. Should there be a military escalation, this would also have a direct impact on the production of semiconductors and the global supply of downstream industries - including those in the EU.

3 Strategic realignment: resilient supply chains and diversification approaches

The Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian war of aggression on Ukraine have once again brought the issue of dependencies in global supply chains to the forefront of corporate and political attention. Due to the supply bottlenecks from 2020, the European Commission has therefore once again analyzed its dependencies and is endeavoring to learn lessons from the crisis. In the industrial strategy updated in 2021, it aims to strengthen the EU's open strategic autonomy and, where necessary, restructure supply chains. Six areas were identified as being particularly critical, including the supply of raw materials and semiconductors [8]. In January 2023, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen also announced the Sovereignty Fund, which is intended to promote 'Made in Europe', particularly in these strategic areas. Similar political approaches are also being pursued in other industrialized nations, with the United States leading the way.

The European Commission wants to reduce excessive dependencies on trading partners - including and especially China (image: Chongqing skyline)

The European Commission wants to reduce excessive dependencies on trading partners - including and especially China (image: Chongqing skyline)

The trade conflict between China and the US has been simmering for over a decade and has been escalating since 2018. The US government is aiming to strengthen its own economic position and become less dependent on China, particularly in strategic areas. Due to the geopolitical events and the associated supply chain disruptions since 2021, it is now pursuing this objective even more vigorously. The semiconductor industry, a strategic sector and important industry in the technology competition with China, is particularly affected. In October 2022, the US Department of Commerce once again imposed far-reaching export restrictions on semiconductors and manufacturing equipment. Comprehensive investment programs were also launched: The CHIPS and Science Act, signed in August 2022, is intended to promote semiconductor production in the country with around USD 52 billion. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) passed by the US Congress a few months later also offers further subsidies, some of which are linked to specific requirements for the domestic procurement of primary products.

The European response followed at the end of 2022 in the form of the EU Chips Act. The EU Commission's proposal aims to promote European innovation and high-tech chip production with around € 43 billion. The German government supports the project and hopes that market leaders in chip manufacturing will set up shop in Germany. Some experts, such as Stefan Kooths from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel), are critical of the plans and consider the chances of significantly increasing the EU's influence in the supply chain to be slim [9]. Precisely because the unbundling of highly integrated supply chains is a challenge, the EU should invest more in promoting international cooperation. This includes transatlantic cooperation in particular. However, talks with the USA are currently proving difficult, as the protectionist measures of the IRA are being criticized in Europe.

However, a focus on production alone is not enough to become strategically more independent in the semiconductor industry. Critical dependencies on mineral raw materials must also be taken into account. In January 2023, the German government presented a key issues paper for a strategic supply of mineral raw materials. In addition to implementing a circular economy, the planned measures include diversifying supply chains and strengthening European and international cooperation [10]. At EU level, the Commission intends to present a legislative proposal on critical raw materials (Critical Raw Materials Act) at the end of March 2023, which is intended to identify improved crisis management and strategies for reducing dependencies. International cooperation is also taking shape. For example, the Mineral Security Partnership (MSP) was launched in mid-2022, an association of around ten industrialized countries, including the USA and the EU, which aims to promote the exchange of information and investment along raw material supply chains.

These joint initiatives thus aim to restructure supply chains - away from China's dominant position and towards a shift in processing to other regions. This is a medium to long-term goal that must be backed up with appropriate financial resources. The interdependence of individual supply chains must also be considered: Without a secure supply of silicon, there will be no production of semiconductors in the EU. This requires coherent industrial policy strategies and, in particular, the strengthening of international partnerships. The extraction of raw materials in particular is often only possible outside the EU due to geological availability. Furthermore, relocating refinery production to these mining countries and establishing or strengthening downstream supply chains there not only makes economic and environmental sense, but is also in the interests of local partners [11].

4 Due diligence obligations for companies: Contributing to resilience in supply chains

In addition to diversifying sources of supply, strengthening resilience in transnational supply chains also requires the creation of transparency and sustainability, both in terms of human rights and the environment. In the traditional supply chain discourse, this strengthening is often contrasted with the hitherto primary goal of increasing efficiency and profits - indeed as a fundamental conflict of objectives. However, experience from the past years of crisis shows that transparency and sustainability must be seen as central components of corporate risk management and contribute to the resilience of supply chains. They should be included as part of a strategic realignment of supply relationships.

Numerous scientific studies show that companies that make sustainability and transparency a central component of their supply chain management are more responsive. They can counter disruptions and other unforeseeable events more quickly, in a more targeted and effective manner and therefore tend to navigate crises better (and more economically). A study by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) from 2021 shows that companies that had already invested in responsible business conduct before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic were more resilient overall [12].

5 Legal anchoring of due diligence obligations: Supply chain laws at national and European level

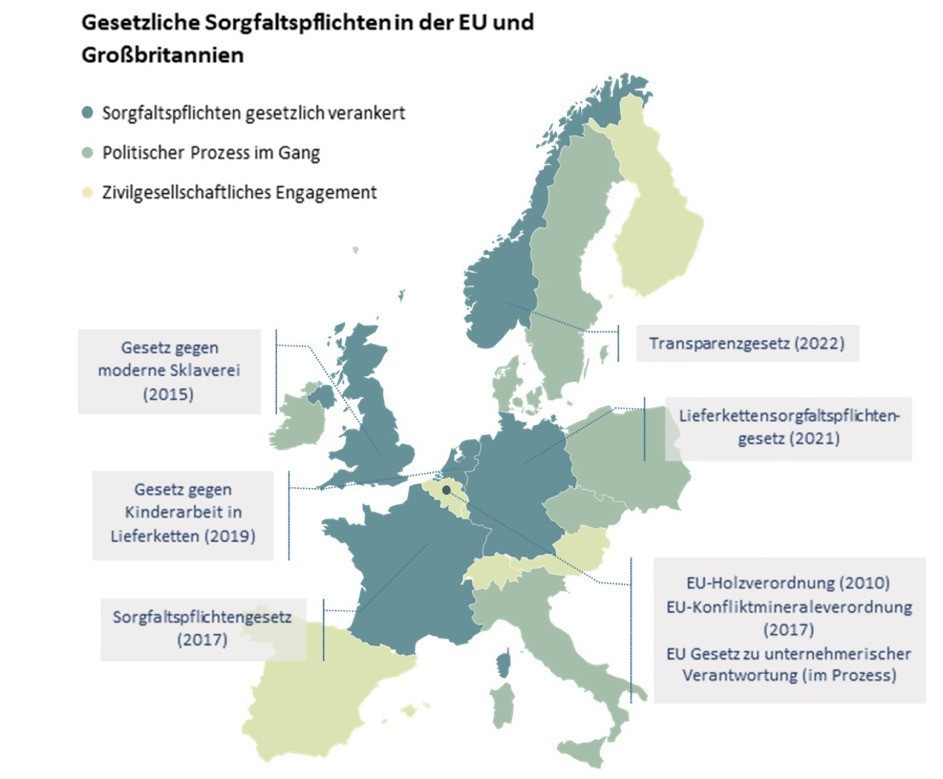

In June 2021, the German Federal Government passed the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG), which will apply for the first time to companies with more than 3,000 employees from January 1, 2023 and to companies with more than 1,000 employees from 2024 [13]. This makes Germany the second country in the EU after France (the French Loi de Vigilance came into force in 2019) to legislate comprehensive cross-sector supply chain due diligence obligations; in many other European countries, such as the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium, similar legislation is currently being discussed or has already been implemented (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Laws and initiatives for due diligence obligations along supply chains in the EU and the UK. Own illustration (as of 2022 / Image: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik)

Fig. 2: Laws and initiatives for due diligence obligations along supply chains in the EU and the UK. Own illustration (as of 2022 / Image: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik)

The EU is also working on a law on corporate due diligence. In March 2022, the EU Commission presented a corresponding proposal (Corporate Sustainable Due Diligence Directive) for a directive, some parts of which go significantly further than the German law. For example, the draft provides for the consideration of the entire upstream and downstream value chain (not just direct suppliers, as stipulated in German law), the expansion of environmental and climate-related due diligence obligations and the civil liability of companies. The so-called trilogue negotiations between the Commission, the Parliament and the Council are currently taking place on the basis of this draft. A final draft law is expected by next year at the latest.

The main aim of the European directive is to create a level playing field, i.e. to guarantee the same high standards and conditions for all companies within the EU. In this way, the EU wants to counteract potential competitive disadvantages between European companies, but also compared to foreign companies that produce in Europe. According to the EU Commission's current legislative proposal, only large companies - approx. 1% of companies based in the EU - are affected, many of which have the necessary resources to implement the regulation or have already established corresponding structures. Often too little consideration is also given to the potential reputational costs for companies that do not comply with their due diligence obligations in the areas of environmental protection and human rights. However, it is also clear that larger companies have more capacity to implement due diligence obligations; accordingly, it is essential to provide sufficient support to smaller and medium-sized companies that are both directly and indirectly affected by these laws. Industry initiatives and multi-stakeholder initiatives such as the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) can support the implementation of the law, while government agencies support companies with handouts, information platforms and exchange opportunities.

It is not only in the EU that there are legal initiatives for due diligence obligations along supply chains. For example, Norway, Canada and Australia also passed their own laws on supply chain due diligence last year. And in important mining countries such as Chile and South Africa, the legal anchoring of social and environmental sustainability in the extraction and processing of raw materials is also progressing. At multilateral level, the aforementioned Mineral Security Partnership names the creation of transparency and sustainability of (raw material) supply chains as one of three key points. In contrast, sustainability has not yet been a key issue in the strategies for semiconductor production.

This leaves the question of the market giant and main competitor China. It remains unlikely that the People's Republic will become an advocate and enforcer of human rights in global supply chains under its current political leadership as a result of a European, let alone German, law on due diligence obligations. But it will increase transparency, because European companies can increase the pressure. The situation is different in the area of environmental sustainability. China has set itself the political and economic goal of moving towards a low-emission circular economy. Accordingly, high environmental regulations within China are already part of Chinese policy today and will become increasingly important. The influence that the EU has on global competitive conditions, particularly in a consortium with other large industrialized countries, should not be underestimated either. European companies will also hold their suppliers to account when reviewing their supply chains, thereby increasing the pressure on Chinese companies. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) adopted by the EU in 2016 serves as a concrete example, which obviously had an influence on the domestic Chinese debate and the subsequent laws on data protection and personal rights. In any case, a European law will increase the transparency of global supply chains, even if it is initially only a matter of identifying previously blind spots along the supply chains.

Conclusion and outlook

Developments over the last three years have shown that our globalized system of closely interlinked supply relationships is highly susceptible to disruption. The cost efficiency of supply chains can no longer be the sole criterion for entrepreneurial action or economic policy strategies. In future, the strategic reorganization of global supply chains must focus more on geopolitical dynamics, the reduction of dependencies and the strengthening of transparency and sustainability. This is the task of both private companies and the state. The former can contribute to strengthening their supply chains through appropriate risk management, the creation of transparency along the supply chain and the implementation of corporate due diligence. The latter can set appropriate framework conditions for the economy, in particular by enshrining due diligence obligations and sustainability criteria in law, through long-term industrial policy strategies for diversification and security of supply and through accompanying extraction and investment programs.

In the mineral raw materials sector and with regard to the production of semiconductors - both areas that are of strategic interest to the EU but are characterized by high dependencies and risks - efforts are already being made to strengthen the resilience of supply chains: The EU Chips Act is being negotiated as part of the European Industrial Strategy; the EU Critical Raw Materials Act is due to be presented at the end of March 2023. The key task for policymakers now is to create coherence between these instruments and between the various national, regional and multilateral levels - and to avoid trade conflicts.

Against the backdrop of the current crises and the debate surrounding the security of supply of critical goods, it is also important that the aspect of sustainability does not take a back seat to diversification efforts. After all, sustainability is a central component of resilient supply chains and therefore also of security of supply. Transparency enables companies to better identify not only existing dependencies but also potential risks, anticipate possible supply disruptions and target diversification opportunities. Particularly in supply chains with high dependency ratios and high-risk suppliers (such as China), proactive risk management is in the interests of both companies and the state.

References

[1] Kiebler, L.; Ebel, D.; Klink, P. ; Sardesai, S.:Risk management of disruptive events in supply chains, Fraunhofer Institute for Material Flow and Logistics IML, Dortmund, 2020, 4, https://www.iml.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/iml/de/documents/OE%20220/Risikomanagement_disruptiver_Ereignisse_in_Supply_Chains.pdf

[2] Müller, M.; Saulich, C.; Schöneich, S.; Schulze, M.: Von der Rohstoffkonkurrenz zur nachhaltigen Rohstoffaußenpolitik, Politikansätze für deutsche Akteure, SWP-Studie 13/2022, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), Berlin, 2022, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/von-der-rohstoffkonkurrenz-zur-nachhaltigen-rohstoffaussenpolitik

[3] Al Barazi, S.; Damm, S.; Huy, D.; Liedtke, M.; Schmidt, M.: DERA-Rohstoffliste 2021, Angebotskonzentration bei mineralischen Rohstoffen und Zwischenprodukten - potenielle Preis- und Lieferrisiken, Berlin, German Mineral Resources Agency at the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (DERA), https://www.deutsche-rohstoffagentur.de/DE/Gemeinsames/Produkte/Downloads/DERA_Rohstoffinformationen/rohstoffinformationen-49.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

[4] UN Comtrade, Export data from 2021, High purity silicon, HS Code: 280469

[5] Doll, F.: This is how important Taiwan is as a chip manufacturer, WirtschaftsWoche, accessed 26.01.2023, 2022, https://www.wiwo.de/unternehmen/it/seitenblick-so-wichtig-ist-taiwan-als-chip-hersteller/28604482.html

[6] Sander, M.; da Silva, G.: Should China really attack the chip stronghold Taiwan, the global economy would be threatened by a catastrophe, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 2022, accessed 26.01.2023, https://www.nzz.ch/technologie/sollte-china-wirklich-die-chip-hochburg-taiwan-angreifen-drohte-auch-der-weltwirtschaft-eine-katastrophe-ld.1654300

[7] Maihold, G.; Mühlhöfer, F.: Unstable supply chains jeopardize security of supply, SWP-Aktuell 80/2021, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), Berlin, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/instabile-lieferketten-gefaehrden-die-versorgungssicherheit

[8] European Commission, European Industrial Strategy, 2020, accessed 26.01.2023, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-industrial-strategy_de

[9] Kooths, S.: Chips Act: EU should not participate in the subsidy race,2022, accessed 26.01.2023, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/de/publikationen/medieninformationen/2022/chips-act-eu-sollte-sich-am-subventionswettlauf-nicht-beteiligen/

[10] Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection, Key issues paper: Pathways to a sustainable and resilient supply of raw materials, 2023, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/E/eckpunktepapier-nachhaltige-und-resiliente-rohstoffversorgung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6

[11] Müller, M.; Saulich, C.; Schöneich, S.; Schulze, M.: Von der Rohstoffkonkurrenz zur nachhaltigen Rohstoffaußenpolitik, Politikansätze für deutsche Akteure, SWP-Studie 2022/S 13, 22.12.2022, p. 17 (© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin, 2020)

[12] OECD, Building more resilient and sustainable global value chains through responsible business conduct, 2021, https://www.oecd.org/corporate/mne/rbc-and-trade.htm#:~:text=Promoting%20policy%20coherence%20between%20responsible%20business%20conduct%20%28RBC%29%2C,the%20gains%20from%20globalisation%20are%20more%20fairly%20distributed

[13] See also Maihold, G.; Müller, M.; Saulich, C.; Schöneich, S.: Responsibility in supply chains: The Due Diligence Act is a first step, SWP Aktuell 2021/A19, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), Berlin, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/aktuell/2021A19_Lieferkettengesetz.pdf

[11] Müller, M.; Saulich, C.; Schöneich, S.; Schulze, M.: From competition for raw materials to a sustainable foreign policy on raw materials, policy approaches for German actors, SWP Study 2022/S 13, 22.12.2022, p. 17 (© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, Berlin, 2020)