At the beginning of the 20th century, a material from the Middle Ages became an important component of the zeppelins that were experiencing their heyday at the time - the so-called "Goldschlägerhaut".

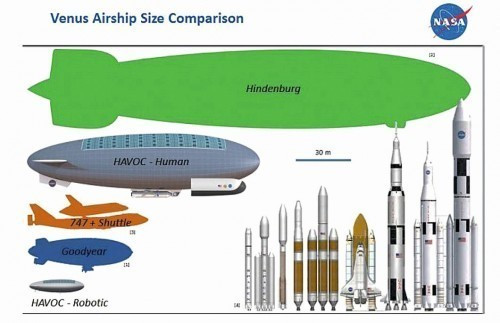

Size comparison of the LZ 129 Hindenburg with carrier rockets for spaceshipsTheera of airship travel began in the 19th century and reached its peak in the first half of the 20th century. Airships were the pioneers of civil aviation. They were the means of transportation of the first airline and also the first aircraft to carry passengers across the Atlantic on a scheduled service without a stopover.

Size comparison of the LZ 129 Hindenburg with carrier rockets for spaceshipsTheera of airship travel began in the 19th century and reached its peak in the first half of the 20th century. Airships were the pioneers of civil aviation. They were the means of transportation of the first airline and also the first aircraft to carry passengers across the Atlantic on a scheduled service without a stopover.

The first rigid airship was developed by David Schwarz in Berlin in 1895/1896. It consisted of an aluminum frame with aluminum planking. Schwarz died before the first test flight. This took place on Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin. The vehicle was irreparably damaged when it landed and was subsequently scrapped [1]. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin was an eyewitness at the time, bought up the patents and designs and patented a design for a "steerable aerial train" in 1898 [2].

Since Zeppelin retired from military service in 1890 at the age of 52, he had only wanted one thing: to build airships. Although several inventors before him had already launched gas-filled balloons into the sky, the development of airships was still in its infancy. Zeppelin wanted to do better. He sacrificed his wife's fortune, collected donations and hired engineers [3].

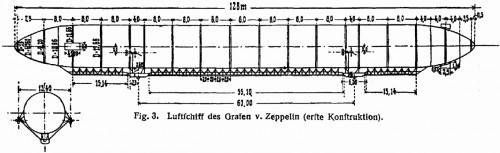

Zeppelin decided to build a rigid airship with a skeleton made of duralumin, a new aluminum material that had only recently become available at the time, to support the interior. The "Zeppelin 1 airship", LZ 1 for short, measured 128 meters with a diameter of 11.25 meters and was reminiscent of a gigantic cigar. Zeppelin filled the air chambers inside with hydrogen, a gas that was much lighter than air - and dangerously flammable. Two gondolas were attached to the underside for pilots, passengers and engines. In order to move forward, Zeppelin's airship had several motor-driven propellers. The airship took off for the first time on July 2, 1900. Thousands of curious people lined the shores of Lake Constance as it ascended with Zeppelin and four other people on board. It flew, but only for 18 minutes before it had to make an emergency landing. The opinion of the experts was that the airship could not be used for military or other purposes [3] .

But Zeppelin did not give up. Five years later, LZ 2 took off, but also had to make an emergency landing on its second test flight. Treetops had ripped open the hull and a storm had done the rest. LZ 3 took to the air barely ten months later. The airship remained aloft for an impressive two hours. People were thrilled and the government in Berlin approved money for the construction of another model, with the requirement that the airship should then remain in the air for a whole day. On July 1, 1908, Zeppelin flew with LZ 4 for twelve hours straight. Newspapers up and down the country reported the story. The giant was soon given its name: "Zeppelin". Three days later, Zeppelin flew another tour over Basel, Strasbourg, Worms and Mainz, finally reaching Echterdingen. But this is where the flight ended. LZ 4, attached to the ground with ropes, was torn from its moorings by an approaching storm. The hydrogen ignited. The airship exploded and burned out completely. A catastrophe! [3] .

And yet, completely unexpectedly, the crash of the "Zeppelin LZ 4" near Echterdingen led to the largest voluntary fundraising campaign in the German Empire, the "Zeppelin Donation of the German People", due to national Zeppelin enthusiasm. Around 6.3 million gold marks (approx. 100 million euros in today's money) were collected in donations from people who believed in him and his invention. An unexpected gift in view of the disaster, which, as it turned out, was the trigger for an entire company empire, parts of which have been preserved to this day in well-known companies via the Zeppelin Foundation. It is certainly fair to say that this Zeppelin donation ignited a kind of German "moonshot" project that triggered the development of technology on a broad basis.

A comparison of the size of the Zeppelin LZ 129 Hindenburg with carrier rockets for satellites for space travel shows the enormous dimensions of the airship and gives a small impression of the challenges that had to be overcome in this "Moonshot" project.

Alongside Zeppelin, the architect who played a decisive role in the development of the Zeppelin Group was Alfred Colsman, who already had contact with Zeppelin through his father-in-law, Carl Berg, and his aluminum-producing company [4].

Immediately after the airship disaster in Echterdingen, Zeppelin called Colsman to Friedrichshafen and made him commercial director and later general manager of his factory (until 1938), which was transformed into "Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin-GmbH" due to the success of the Zeppelin people's donation at the time. Under Colsman's leadership, the Zeppelin shipyard in Friedrichshafen grew into one of the largest companies in southwest Germany, with 17,000 employees. Suppliers and component developers, some of which were later to become global companies, emerged, such as Maybach-Motorenbau, Maybach-Zahnradfabrik-AG Friedrichshafen, Ballonhüllen-Gesellschaft (Staaken), Zeppelin Wasserstoff- und Sauerstoff-AG (ZEWAS) and Dornier-Flugzeugwerke. Alfred Colsman thus became the architect of the Zeppelin Group and a pioneer of industrial development in the Lake Constance region [4].

![Aufbau einer Zeppelin-Gaszelle [5] Aufbau einer Zeppelin-Gaszelle [5]](/images/stories/Abo-2020-09/thumbnails/thumb_gt-2021-09-0048.jpg) Construction of a Zeppelin gas cell [5]

Construction of a Zeppelin gas cell [5]

Colsman also founded the "Zeppelin-Wohlfahrt-GmbH" (1913), which built the "Zeppelin Village" for members of the Group's workforce, and the "Oberland Milchverwertung" company in Ravensburg [4].

Saving weight was also an important and constant theme in the development of the Zeppelins.

The LZ 129 Hindenburg had 16 hydrogen-filled gas cells made of film or fabric skin. They had a special fold guide to ensure that they lay down properly when inflated and to prevent unwanted movement when not inflated. The maximum total volume was 200,000m3. Despite the weight-saving materials, the gas cells had a total weight of 11,546 kg due to their enormous size [5].

In Zeppelin's so-called "Tafelrunden", "... in which almost every innovation in the field of airship travel that was attempted or realized sooner or later ... was discussed ..." [4]. [4], there was also early talk of a Goldschläger skin, which was expected to save an extremely important amount of weight in airframe construction for the Z airships, but which no one was able to produce industrially at that time [4].

![Produktion des LZ 129 „Hindenburg“ [5] Produktion des LZ 129 „Hindenburg“ [5]](/images/stories/Abo-2020-09/thumbnails/thumb_gt-2021-09-0047.jpg) Production of the LZ 129 "Hindenburg" [5]

Production of the LZ 129 "Hindenburg" [5]

Design drawing of the first of all zeppelins, LZ-1

Design drawing of the first of all zeppelins, LZ-1

The name "gold beater skin" comes from the fact that gold beater skin had already been used before in the production of gold leaf, known as gold beating. The first gold beaters appeared in Germany around 1400 as independent craftsmen. Over time, gold leaf production was concentrated in the cities of Nuremberg, Fürth and Schwabach. In the 19th century, 70% of the population in Schwabach worked in this trade and Schwabach became a "gold beater town". In 1996, the DGO Precious Metals Committee visited the Noris company, which has existed in Schwabach since 1876, to gain an impression of the complicated production of gold leaf, which requires a great deal of process know-how.

The loss of the previously very reliable airship "Schwaben" had increased the development of the production of gold beater hides in the required quantities and qualities to the highest level. "The 'Schwaben' had been anchored on Düsseldorfer Platz in a thunderstorm and hit the ground hard with the front boom, breaking some struts and damaging one of the rubber cells." The immediate search for the cause quickly revealed that the rubbing of the cell surfaces had caused finger-length sparks, which had ignited the escaping hydrogen. This was also the cause of earlier fire damage to their airships [4]. The solution was now the gold beater skin, with which initial tests had already been carried out.

Using all their strength, they succeeded in producing usable gold beater skin cells. The cells were particularly light, tear-resistant and gas-tight. Goldbeater's skin was made from the outermost skin layer of sheep, pig or cow intestines. Bovine intestinal hides were used in the majority of cases. The intestines were washed and the top layer of skin was peeled off. The skins were then stretched over a mold, dried, washed with alum water and finally coated with egg white, which served as an adhesive. Initially, around seven or more layers were glued on top of each other, but later the number of layers was reduced to around four. After experimenting with pure goldbeater's skin, a combination of goldbeater's skin and gauze quickly became established. One layer each of gauze and goldbeater's skin alternated. These were also known as fabric skins. Machine production was not possible; a great deal of manual labor was required. This was another reason why production was very expensive, and many of the skins had to be imported for reasons of supply and quality. The appendix skins of around 50,000 animals were required for a single gas cell, and around 700,000 skins were needed for a complete airship. The total surface area of the gas cells in an airship like the LZ 127 was an impressive 56,878 m² [4, 5].

In 1910, the first gas cells made of gold-beater skin were tested at Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH. After initial quality problems, good results were quickly achieved. In 1913, the first airship (LZ 18) was completed with gas cells made entirely of gold-beater skin.

In 1915, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH founded Ballonhüllen-Gesellschaft mbH in Berlin-Tempelhof for the production of gold-beater skin in order to be able to manufacture the required quantities of gold-beater skin. Gas cells made of gold beater skin were used until LZ 127 "Graf Zeppelin".

The largest airships ever were the LZ 129 "Hindenburg" and its sister ship LZ 130 "Graf Zeppelin II" with a length of 245 meters, a hull diameter of over 40 meters and a capacity of around 200,000 cubic meters of hydrogen carrier gas. The "Hindenburg" could carry 50-70 passengers over a distance of 17,500 kilometers.

On May 6, 1937, the "Hindenburg" burst into flames on landing in Lakehurst/USA, killing 36 people. Although this accident was not the most serious in airship travel, the "Hindenburg disaster" went down in history as one of the great technical accidents. It was also the last accident involving a rigid airship. The approaching Second World War ended the era of fixed-wing airships.

Since then, air traffic has been dominated by commercial aircraft, whose technology had made great progress in the 1930s and 1940s. In the last years of his life, Zeppelin, together with Gustav Klein, a former designer at Bosch, and Claude Dornier, worked intensively on the construction of airplanes, even flying boats, because he saw the future in airplanes. Count Zeppelin was therefore also a pioneer in this field.

The gold mallet skins are still used today by oboists to seal their mouthpieces due to their good elasticity, so that no air escapes between the two reeds of the mouthpiece. Oboists colloquially refer to the gold beater skin as fish skin [6]. -Uwe Landau

Literature

[1] Wikipedia: Rigid airship

[2] Wikipedia: Zeppelin

[3] Verena Linde: Zeppelins: Giants of the sky, Geolino No. 08/14

[4] Alfred Colsman: Airship ahead! Arbeit und Erleben am Werke Zeppelins, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt (1933)

[5] https://www.hi.uni-stuttgart.de: Gas cell material history of the Zeppelin: 220 tons - lighter than air;

[6] Wikipedia: Goldschlägerhaut

[7] Maiken Nielsen: How a Sylt resident survived the crash of the Hindenburg, Sylter Rundschau, reading on Sylt, October 26, 2016