Maintenance and care of various cultural assets require special care and gentle handling, especially of surfaces. A new type of foam made from a sugar surfactant is effective and biodegradable.

Dr. Heinrich Piening undoubtedly has one of the most beautiful jobs that the German working world has to offer. The deputy head of the Restoration Center of the Bavarian Administration of State Palaces, Gardens and Lakes (incidentally the largest museum operator in Germany) works in the heart of Munich - in the south wing of Nymphenburg Palace. He and the department's 50 or so employees are responsible for the care, maintenance and upkeep of various cultural assets, including 40 carriages, some of which are magnificent. The oldest dates back to around 1720, while the newest was built during the First World War.

Sisyphean task: Dr. Heinrich Piening tackles the dirt on a historic carriage with a cotton bud Photo credit: Heinz Käsinger / released by the Bavarian Palace Administration www.schloesser.bayern.de

Sisyphean task: Dr. Heinrich Piening tackles the dirt on a historic carriage with a cotton bud Photo credit: Heinz Käsinger / released by the Bavarian Palace Administration www.schloesser.bayern.de

A carriage as expensive as 20 farms

"A carriage like this used to be an act of state on wheels," smiles Piening. "Today, it's perhaps only comparable to a one-off Rolls Royce." In fact, in the middle of the 19th century, such an early high-tech product cost up to 180,000 marks. At the time, that was roughly equivalent to the value of 20 farms.

Restorers always pay particular attention to the diverse surfaces of cultural assets. For example, a particularly lavishly decorated carriage belonging to King Ludwig II, the fairytale king, is almost completely gilded. In fact, given the different materials used, different coating methods were also used. Restorer Piening: "We can already find galvanized surfaces on some metal parts at that time. Mostly, however, metals were still fire-gilded at that time." And the predominant wooden surfaces? "They were covered with gold leaf," says Piening.

But gold leaf is not weatherproof. The designers of the time had to come up with something. After all, varnishes with the properties we have today were not yet known back then. The solution was layers of opal and amber, ground up and boiled with resins and oil - so-called kople, a semi-fossil resin from Africa or East Asia. The result was such an effective surface protection that this early varnish not only made state coaches suitable for outdoor use, but was also used as a varnish in railroad carriages until well into the 1950s. It was only then that sanding varnishes for sealing wood finally became established.

In Bavaria, the Palace Administration is responsible for exhibiting and preserving the cultural assets of the Wittelsbach dynasty. The carriages in question have been standing in the stables of Nymphenburg Palace for more than 100 years, gathering the proverbial dust. They are no longer moved, they are too valuable for that. Dr. Piening and his team are therefore also responsible for keeping the precious objects clean. He explains: "It's a mixture of five different types of dirt that we have to contend with. Mineral dirt, soot and rubber residue, grease, salts and fibers." Cleaning must therefore always be customized. In the case of salts, aqueous agents are used; grease is removed with solvents. Aggressive chemical or mechanical applications, such as scrubbing with chlorine cleaners, are taboo - in the most extreme cases. Instead, the cleaning method must also be customized. Piening mentions the application of cleaning agents using compresses or gels. And it was in this context that he came up with the idea of trying foam.

This sledge was the first electrified vehicle in the world. The lantern light was powered by a battery

This sledge was the first electrified vehicle in the world. The lantern light was powered by a battery

Today, six people work permanently on the project

Even the first attempts were successful; the restorer had the feeling that he could get certain areas cleaner with less effort using foam than with a compress or gel, for example. His interest was piqued and he approached Strasbourg professor Wibke Drenckhan, a proven expert in foam cleaning, with his problem - and provided a possible solution at the same time. Professor Drenckhan discussed the matter with Professor Cosima Stubenrauch, Dean of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Stuttgart, at a congress. Stubenrauch laughs: "We decided at the time that we found the matter exciting."

Between an "exciting thing" and a research project, however, there is usually a hurdle called money. And this is where the Osnabrück-based German Federal Environmental Foundation (DBU) comes into play. Professor Stubenrauch had discovered that in this case it is not only possible to achieve a significant reduction in the consumption of cleaning agents (up to 90%), but also to work with biodegradable products. Dr. Piening already works with a sugar surfactant on site in Munich. This fact ultimately led to the DBU supporting the research project with 120,000 euros. The Osnabrück team now runs the project under the catchy and humorous title "The King's New Foams." Six people are now working on the project on a permanent basis, at times even up to 15 people, and further cooperation partners are being sought.

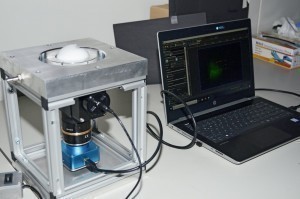

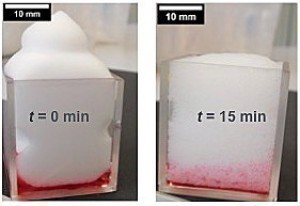

Dean Stubenrauch is thinking on a large scale. She envisions a washing system that produces the foam on site, just in time and in the desired quality, and applies it to the object to be cleaned. PhD student Tamara Schad is in charge of the project at the university. She and the dean have designed an apparatus to observe and qualify the processes. To put it simply, a camera is mounted under a frame that is kept transparent at the top by a glass plate and connected to a computer. An additional blocking filter is mounted between the camera and the glass plate. This ensures that the camera only captures luminescence, but not ambient light. The slide is now artificially soiled with sunflower oil. The oil is mixed with a luminescent substance. When the cleaning foam is applied to the oil, it can be observed on the screen how the foam absorbs the contaminated oil.

The scientists in Stuttgart now know that not all foam is the same. A comparatively hard, dry foam with small bubbles works best. Schad: "It will be an exciting task for an engineer to build a machine that can produce this foam in the desired quality at any time."

The cleaning apparatus in the lab. PhD student Tamara Schad applies the cleaning foam to the slide. The foam draws the dirt from the surface into itself. Prof. Dr. Cosima Stubenrauch is the project leader

Another goal of the Stuttgart scientists is to produce a foam that disappears by itself. In practice, in the Munich stables of the palace, the foam is vacuumed away after its application time.

Both teams, in Munich and Stuttgart, are optimistic that after another two years of research, something will have emerged. Piening: "And that is urgently needed. Cleaning a large carriage with compresses and cotton buds alone takes up to 1000 working hours. You can just start again at the front when you've finished at the back."

What happens next? Cosima Stubenrauch in Stuttgart is hoping to get a relevant company on board. We are talking about cleaning specialist Kärcher, for example, which has already signaled its interest. And in Munich's Nymphenburg Palace, in typical imperial serenity: "Let's see."