Approval procedures for surface treatment plants are taking up more and more time and resources. The risk-based approach has become less important and has been replaced by an ideology of zero risk, as formulated by the German Social Accident Insurance Institution for the chemical industry (BG RCI) in the Zero Vision.

For example, the draft of the new IED Directive states that the lowest (safest value) must always be used for concentration ranges, and deviations from this must be justified and proven by the operator. This development gives rise to the issue of increasing complexity [2] and unpredictability.

The trend towards complexity

Approval procedures have become increasingly complicated [1] in recent years, as legislators and other institutions have issued an increasing number of regulations and published sources of information that define various requirements for surface operations.

Due to the frequent lack of coordination between these rules and their publication in different places, it is difficult to maintain an overview. In addition, there are regulations that are based on dynamic data (e.g. the CLP Regulation or REACH).

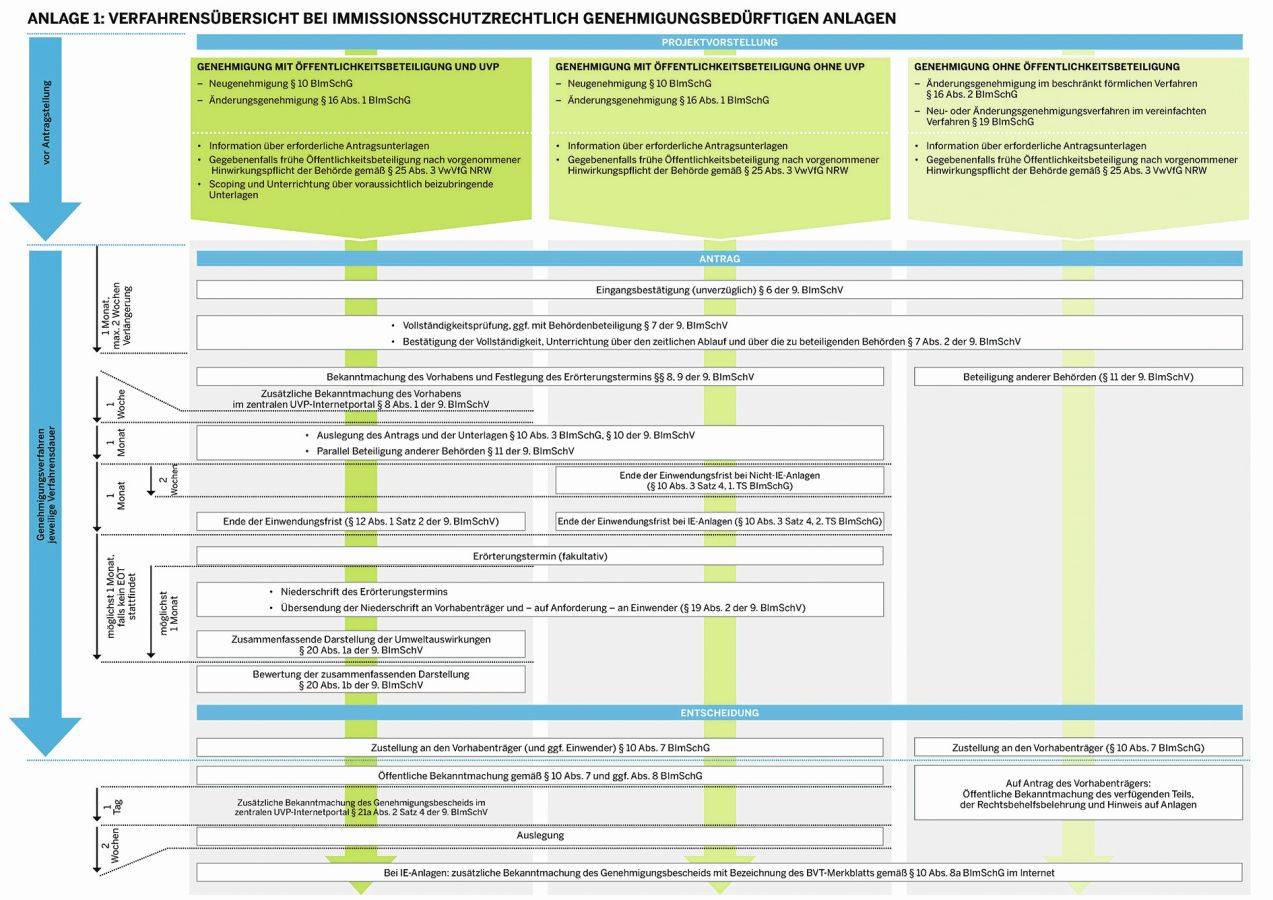

Fig. 2: Overview of BIMSchG procedures (7)

Fig. 2: Overview of BIMSchG procedures (7)

This trend is currently continuing or even appears to be accelerating and is leading to authorization procedures developing into so-called "complex systems".

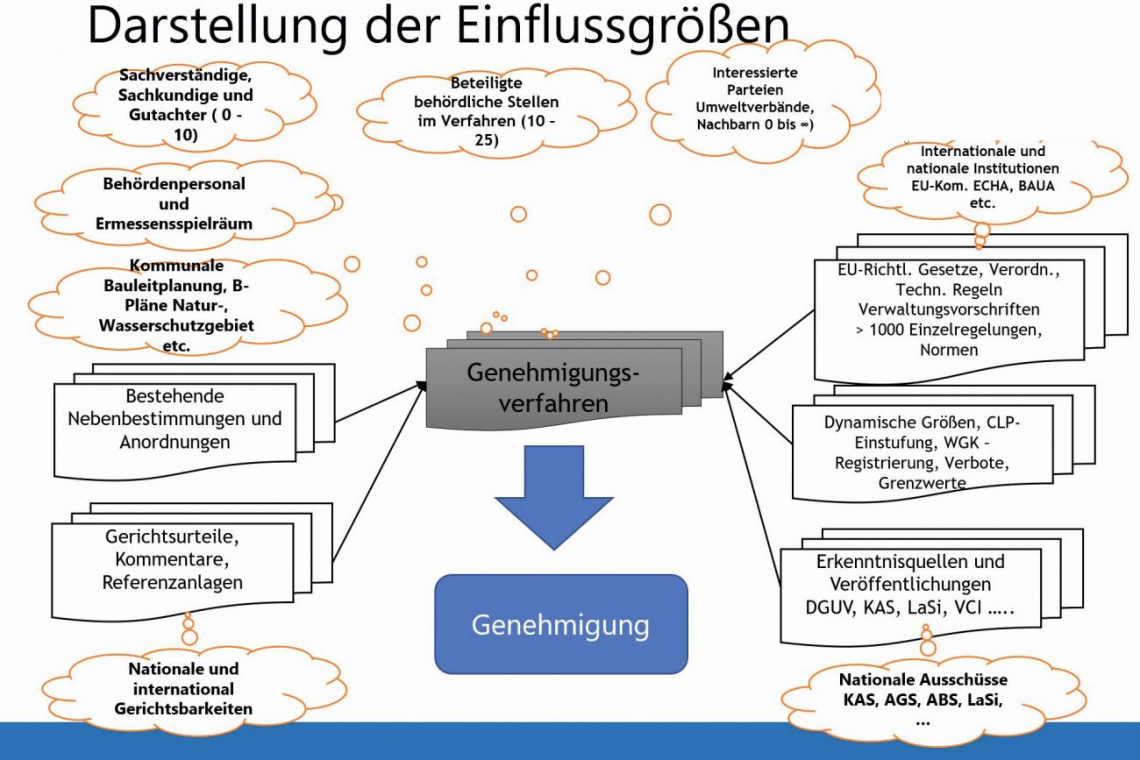

In other words, an approval procedure is increasingly becoming a kind of lottery with unpredictable odds. The complexity reaches a degree of interaction that no longer allows a reliable overall prediction. The causes of complexity are (Fig. 1):

- Increase in the number of parties involved in the process

- Increase in the number of interested parties exerting influence (e.g. environmental associations, neighbors, etc.)

- Increase in the number of laws, ordinances and administrative regulations to be taken into account

- Increase in the number of sources of knowledge that can have an influence

- Dynamic basis for legal regulations, e.g. CLP Regulation, REACH etc.

- Lack of clarity and gaps in the regulations as well as outdated regulations, e.g. Extinguishing Water Retention Directive

- Number of legislative bodies and other publishers of sources of knowledge

- Number of committees that create sources of knowledge and sub-legislative regulations e.g. DGUV

- Unclear and bloated administrative staff structures

- Discretionary scope of the authority in the application of sub-legal regulations

- Increase in the number of expert opinions requested by the authorities in proceedings, etc.

Interactions

The individual regulations would be easy to implement on their own, but there are interactions between the regulations that are not apparent at first glance. Here are just a few examples:

Industrial chemistry in surface technology

- Classification of substances in water hazard classes (UBA)

- Classification of mixtures - chemical supplier or operator

- Use or storage of substances hazardous to water

- AwSV system - hazard level based on substance quantities and WGK (WHG, AwSV)

- Definition of containment areas and retention facilities

- Structural requirements (DWA 786, DiBt guidelines) -> Requirements for structural design/substructure design in concrete construction

- Definition of the requirements for the sealing surfaces. Requirement of coatings etc.

- Fire protection concept

- Information on extinguishing agents, extinguishing agent quantities - thus influence on extinguishing water retention

- Escape and rescue routes - modification of walkways - obstacles due to permanent thresholds

- Definition of fire compartments etc.

- Occupational safety vs. water protection

- Requirements, e.g. of trades that must be fixed to the ground - must also meet water protection requirements

The water hazard classes of substances are legally classified on application by the UBA and published in the so-called Rigoletto [8]. Mixtures are generally classified by the supplier and documented in the safety data sheet. Mixtures that the operator manufactures himself must be classified himself in accordance with the AwSV.

Depending on the number and quantity, the reclassification of a substance or mixture may mean that the entire design of the system must be changed. A change of supplier can also lead to this (Fig. 2).

Dynamic basis for legal regulations

- In addition to the WGK already mentioned, there are many dynamic influences that can pose a risk for the planning of the plant and the application procedure - this is also only an incomplete list:

- Classification of substances and mixtures

- CLP

- Classification harmonized by the manufacturer

- ATPs - Adaptation to Technical Progress

- Urban land-use planning

- Area designations - development plans

- Appropriate distance and approaching residential development

- Protected areas of all kinds

- Water protection areas

- FHH areas, biotopes etc.

- Fauna and flora worthy of protection: hamsters, bats, etc.

- Neighbors and interested parties

- Objections - protection claims

- Traffic situation

The problem with dynamic influences is initially the difficulty of incorporating them into the planning, as it is almost impossible to monitor all sources. Influencing factors coming from manufacturers or interested parties are particularly difficult to assess.

Furthermore, Section 67 [4] of the Federal Immission Control Act states: "Procedures that have already begun must be completed in accordance with the provisions of this Act and the legal and administrative regulations based on this Act." This means that a new legal requirement that has suddenly arisen must be implemented in ongoing proceedings.

This means that if, for example, a change in classification leads to an additional requirement in the procedure, the application and the planning may have to be revised. This can lead to considerable delays or even to the planning being overturned, as all the necessary changes have to be reassessed by the authority.

Vagueness and gaps in regulations

The legal regulations and their interpretation repeatedly allow for different interpretations. For example, there are uncertainties in explosion protection as to whether in certain cases, if flammable substances are present but no Ex zones are designated due to the technical measures, tests must still be carried out in accordance with Annex 3 of the Ordinance on Industrial Safety and Health.

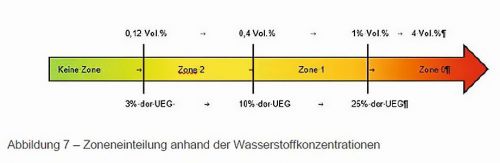

Fig. 3: Classification of explosion zones

Fig. 3: Classification of explosion zones

In such cases, the discretionary scope and the opinion of the competent authority or the personal view of the approval are important. However, if this does not agree with the application or the system planning, there is a risk of discussions involving experts and appointed experts. The result is, of course, a considerable loss of time in the process. In the worst-case scenario, even the courts may have to clarify the facts.

Publications by associations and working groups

There are many national and international publications, e.g. from the DGUV, BfR, VCI etc., which are intended to help clarify legal issues. The papers are usually produced in closed working groups whose composition is determined more or less arbitrarily by the publisher. Involvement of the industries or other affected parties is often at the discretion of the authors.

Although such papers are usually benevolently declared to be working aids or collections of examples, they are also referred to in application procedures for official approval and implementation is required. The current trend of using computer simulations or AI to clarify system design issues is particularly critical.

As a result, if the planning does not follow these sources of knowledge, the operator is forced into a reversal of the burden of proof and must now explain why the guidance used is not applicable in their case. This means that a system that actually conforms to the Product Safety Act (CE-compliant) is not approved due to the use of a working aid in the procedure. Here too, contradictions in the rules and regulations and ambiguities in practical application become apparent.

An example of this is the FBHM 122 [9] guidance document published in March 2022. Here, a completely new zone model was developed for electrolytes with hydrogen evolution based on a master's thesis on CFD simulation. The result is that explosion zones must also be defined below the lower explosion limit (LEL, in this case 4 % H2).

In order to avoid such a zone, the H2 concentration would have to be reduced to below 0.12 % by means of ventilation measures. This can lead to volumes of over 10,000m3/h for electrolytic processes and standard dimensions, e.g. 3 x 1 meter bath surface.

Section 7 of FBHM 122 reads: "Summary and application limits: This 'Subject Area Current' derives examples of hazardous areas in electroplating plants and assists in the preparation of explosion protection documents."

Although it is made clear that this is a collection of examples and not the state of the art, this paper is already being used by authorities and operators are encouraged to act accordingly (Fig. 3).

Risk assessment and conclusion

Looking only at the examples given here, it quickly becomes clear that large-scale licensing procedures in particular are no longer just complicated, but must be treated as sensitive systems that are on the verge of emergence [3]. Even if all technical details have been clarified and are within the legal framework, the outcome of a procedure can no longer be predicted with certainty. Even small changes or dynamic parameters can lead to major delays and possibly to the approval procedure and the planned project being overturned. This raises the question: How will companies deal with this in the future?

Options for reducing complexity

The following points are intended to provide pointers on how to reduce complexity before and during the procedure:

- Clearly define the subject of the application

- Keep the written form of the application simple

- Clear technical specification of the planned installation

- Design coordination with the authority

- Inform interested parties in advance

- Identify statutory and sub-statutory regulations and sources of information

- Clarify interactions

- Include dynamic legal bases as far as possible

- Address ambiguities and gaps in regulations with the authority in advance

- Determine the authority's scope of discretion and the need for expert opinions.

Subject of the application

- It is important to clearly define the subject of the application in one sentence.

- The wording should leave as little room for interpretation as possible.

- The wording must be identical on all included applications (e.g. building application)

- If possible, there should only be one application item!

- If several application items are defined, the authority will examine each one individually. Approval will only be granted once all application items have been checked with a positive result.

Written form

- It is worth discussing the structure and layout of the application with the approving authority.

- Some authorities even issue checklists for this purpose.

- Avoid prose. Only if facts need to be explained in order to be understood should this be done in a concise, unambiguous form.

- Reduce content. The application should only contain what is necessary for the authority's examination.

- Avoid flowery wording

- Do not explain facts that are not the subject of the application

- Comprehensible derivation!

- Facts must be clearly derived from sources and planning documents. Mere assertions, e.g. our "air emissions are in the range of de minimis mass flows", are not expedient; they must be clearly substantiated

- Completeness

- Even if the content is brief, the scope and level of detail must be such that the approval and the bodies involved can examine the application and make a decision

Specification of the planned system

- Only submit the application once all relevant specifications have been defined

- Subsequent changes after submission are the death of any procedure

- Particularly in the case of extensive applications, it is almost impossible to inform every body involved in a timely manner and to exchange the documents

- In most cases, this leads to the application being resubmitted and the submitted application being withdrawn

Draft coordination with the authority

If the authority is open to it, agree the draft application with it. This can also take the form of an application conference, where critical topics and content are agreed in advance. The time invested here usually pays off in the end by significantly reducing the number of additional claims. If it makes sense, you should also coordinate with the bodies involved for the technical participation, including

- AwSV team

- Waste water

- Waste

- Occupational health and safety

Vagueness, legal loopholes and interested parties

This point should be viewed critically. The applicant should have a good picture here of whether there is a good relationship with the interested parties (e.g. neighbors). In the best case, this information in advance can reduce the number of objections in the public procedure. In the worst-case scenario, the attention of potential objectors can be drawn here in the first place.

The number of bodies issuing rules is increasing rapidly, as is the number of rules being issued. Examples include

- Inspection obligations in accordance with BetrSichV or AwSV

- Multiple regulations from different publishers (TRGS vs. DGUV)

- Outdated regulations, e.g. extinguishing water retention guidelines

The applicant should clarify these possible ambiguities with the authority in advance as far as possible or submit the application in such a way that these ambiguities are not affected. Otherwise there is a risk of unpleasant, time-consuming discussions.

If facts are not defined by legal regulations, the authority can clarify facts at its own discretion. However, experience has shown that the authorities' ability to reach a final decision is limited, which is why experts come into play. It should not be concealed that some of the expert opinions are also required by the regulations themselves, e.g. Section 41 AwSV. The number of expert opinions in approval procedures is constantly increasing anyway. More expert opinions lead to more complexity, as each expert has a different perspective and is dependent on the information that is provided. In the worst-case scenario, this can lead to disputes between experts and with the applicant.

The applicant should therefore try to keep the number of expert opinions as low as possible, including in discussions with the authority.

Furthermore, great care should be taken when selecting experts. The expert should know the subject area well. An AwSV expert who mainly inspects filling stations and oil tanks is certainly the second choice for a surface coating.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, the trend on the part of the government and certain interest groups to regulate the implementation of industrial projects more strictly is unbroken. Despite constant government announcements to deregulate and simplify, the exact opposite is actually happening.

Although, as the article shows, plant operators can take measures to reduce complexity, this will not be enough to restore adequate planning certainty in the future.

Hence the clear message to the legislative bodies and interest groups to act sensibly here and actually reduce bureaucracy rather than imposing ever more protection requirements, the benefits of which have long been barely measurable. If Europe wants to continue as an industrial location with the associated prosperity, we must accept risks at an appropriate level.

The article is based on a presentation at the Surface Days in Berlin 2023.

INFO

Statutory and sub-statutory regulations (examples)

Legal register and monitoring of legal development; monitoring of the development of the legal framework at all levels; EU (e.g. BAT decisions); federal laws; state laws; administrative regulations (TA-Luft, TA-Lärm...); technical regulations (TRGS, TRBS, TRBS etc.); local authorities (statutes, development plans, distance classes, protected areas, urban land-use planning); DGUV (BG)

Literature

[1] https://www.wortbedeutung.info/kompliziert/

[2] https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Komplexität

[3] Wicker Trust as a mechanism for reducing complexity https://web.archive.org/web/20131126021905/http://www.anthro.unibe.ch/unibe/philhist/anthro/content/e297/e1387/e5049/e5128/linkliste5129/09hs-dijana-tavra_ger.pdf#

[4] Luhmann, Niklas (1998): "Complexity", in: Luhmann, Niklas, Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft. Erster Teilband, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Verlag, 134-144.

[5] Luhmann, Niklas (2005): "Komplexität", in: Luhmann, Niklas, Soziologische Aufklärung 2. Aufsätze zur Theorie der Gesellschaft, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/ GWV Fachverlage GmbH, 255-276.

[6] Steven Johnson: Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities. Scribner, New York 2001,

[7] Das Genehmigungs- und Anzeigeverfahren nach dem Bundes-Immissionschutzgesetz (Leitfaden für ein optimiertes und beschleunigtes Verfahren in NRW) Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Transport 2nd edition February 2023

[8] Rigoletto https://webrigoletto.uba.de/rigoletto/ Federal Environment Agency, Division IV 2.6, Substances Hazardous to Water, Wörlitzer Platz 1, 06844 Dessau-Roßlau

[9] FBHM 122 https://publikationen.dguv.de/regelwerk/publikationen-nach-fachbereich/holz-und-metall/oberflaechentechnik/4620/fbhm-122-hilfestellungen-zum-explosionsschutzkonzept-und-zur-zoneneinteilung-fuer-explosionsgefaehrde, March 31, 2022, BGHM, Surface Technology Division. Published by: German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV)