Not only did philosophy, poetry and painting flourish during the Romantic period, but also the natural sciences. Although the Romantics rejected the Enlightenment as a soulless turn to science, Theodor Grotthuss (article will appear in the next issue) and J. W. Ritter are regarded as the actual founders of electrochemical theory.

More than 100 years before the first publication of "Galvanotechnik", there had already been a series of publications in Germany dealing with galvanism. Publishing such a journal was the only way for a certain Johann Wilhelm Ritter to earn some money. But from the beginning.

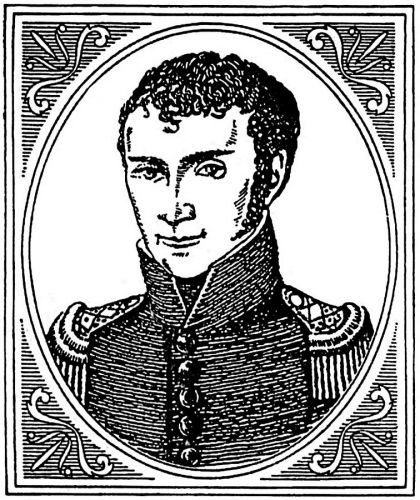

Johann Wilhelm Ritter, a late picture. It shows him in the uniform of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, so the picture must have been taken in Munich after 1805Theyear was 1776. At the beginning of December, it had become bitterly cold in the small town of Samitz in the Lower Silesian Plain. The thermometer did not rise above -20 °C until well into the new year. On the 16th of the month, at eleven in the evening, the 23-year-old wife of the local pastor, Juliane Friederike Ritter, gave birth to a boy. The parents give him the father's name, Johann Wilhelm. The constellation of the stars is not bad on that day in December. The sun is in the sign of Sagittarius and tends towards Mars and Neptune. Little Johann Wilhelm can expect deep insights, talent in science and mathematics, but above all spiritual freedom in his life. This astrological component is worth mentioning, as Ritter would later become enthusiastic about esoteric subjects such as astrology and siderealism.

Johann Wilhelm Ritter, a late picture. It shows him in the uniform of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, so the picture must have been taken in Munich after 1805Theyear was 1776. At the beginning of December, it had become bitterly cold in the small town of Samitz in the Lower Silesian Plain. The thermometer did not rise above -20 °C until well into the new year. On the 16th of the month, at eleven in the evening, the 23-year-old wife of the local pastor, Juliane Friederike Ritter, gave birth to a boy. The parents give him the father's name, Johann Wilhelm. The constellation of the stars is not bad on that day in December. The sun is in the sign of Sagittarius and tends towards Mars and Neptune. Little Johann Wilhelm can expect deep insights, talent in science and mathematics, but above all spiritual freedom in his life. This astrological component is worth mentioning, as Ritter would later become enthusiastic about esoteric subjects such as astrology and siderealism.

His father had planned a spiritual career for him, but his son was not interested and the family did not have the money to study theology. He attended Latin school until he was 14 and then completed an apprenticeship as a pharmacist. During this time, he came into contact with the writings of Galvani and Volta. He devoured them voraciously and now knew that being a pharmacist was not necessarily what he wanted to do with his life. Especially as running his own pharmacy was far from the family's financial reach.

Ritter is penniless. Nevertheless, he leaves his parents' house. He would never see it again. A friend of the family later wrote: "The parents could help him with nothing but their blessing as he entered the world." And so, on April 27, 1796, when he was almost 20, he enrolled in Jena with empty pockets to study natural sciences (under "Joan. Guilielm Ritter, Silesius"). Little did he know that he already had half his life behind him.

One of his early teachers, whom he would admire for the rest of his life, was the Jena court councillor Professor Voigt. Ritter studied physics and applied mathematics with him. Although he felt drawn to the latter, he was unable to find the right approach. Duke Ernst II offered Ritter a mathematics scholarship, which the young student did not take up. Ritter can be blamed for this today. Many of his findings therefore remain based on experimentation, without him having placed them on the infallible foundation of mathematics. Many of his experiments are therefore not reproducible.

Immediately after beginning his studies, Ritter began experimenting in the field of galvanism. It was Voigt who supported him, as the professor also carried out galvanic experiments. Ritter was allowed to use all of his teacher's laboratory equipment. He quickly gained a reputation as an expert in this field. Just one year later, the Prussian mining assessor Alexander von Humboldt became aware of Ritter. He asked him to edit his book "Versuche über die gereizte Muskel- und Nervenfaser nebst Vermutungen über den chemischen Prozess des Lebens in der Tier- und Pflanzenwelt" and to do so "with critical rigor and to note where he had erred or expressed himself too one-sidedly". Ritter set to work with great enthusiasm.

At the same time, he writes his own book. Entitled "Beweis, dass ein beständiger Galvanismus den Lebensprozess im Tierreich begleite", it was published in 1798. At the time, the phenomenon of galvanism was not yet concerned with the coating of materials. It was about nothing less than life itself - above all about whether electrical currents are actually responsible for the movements of muscles (including the heart) - and if so, how and why. Medical applications are the focus of interest.

Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta began to argue about this in faraway Italy. Ritter's work took place in the middle of this debate, which later became known as the Galvanism Controversy. Luigi Galvani was a doctor. In this capacity, he was of the opinion that a special animal electricity (fluidum) caused muscles to contract. Volta was a physicist. What counted for him was the observation that muscles only twitched when an external current was applied.

Ritter, on the other hand, was a universal genius. He was interested in both theories. Finally, he focused his attention on possible electrochemical processes in the preparation, i.e. in a muscle. He was thus able to show that neither the mere contact of two metals (Volta) nor a mysterious fluid (Galvani) was the cause of electrical voltage differences. Rather, Ritter recognized the reason in chemical reactions that take place between metal and electrolyte (the salty body fluid in the preparations). He thus combined the two theories of the Italian scientists.

"Ritter was one of the most splendid natures ever" Brentano

Ritter's early death was attributed by his friends to the numerous self-experiments he subjected his body to. Today it is assumed that it was consumptionRitterhad acquired an excellent scientific reputation early on. The penniless student moved in the highest circles. His friends (and patrons or even creditors) included such illustrious personalities as the poet Clemens von Brentano, the philosopher Friedrich Schelling, the linguist August Wilhelm Schlegel and the mining assessor Friedrich von Hardenberg. The latter wrote mystical-romantic poems under the pseudonym Novalis. His volumes of poetry are bestsellers. Novalis writes to Caroline Schlegel, the beautiful wife of August Schlegel (with whom he is madly in love): "Knight is knight. And we are only his squires." And Brentano, after Ritter's death, to Görres: "Ritter was one of the most wonderful natures ever."

Ritter's early death was attributed by his friends to the numerous self-experiments he subjected his body to. Today it is assumed that it was consumptionRitterhad acquired an excellent scientific reputation early on. The penniless student moved in the highest circles. His friends (and patrons or even creditors) included such illustrious personalities as the poet Clemens von Brentano, the philosopher Friedrich Schelling, the linguist August Wilhelm Schlegel and the mining assessor Friedrich von Hardenberg. The latter wrote mystical-romantic poems under the pseudonym Novalis. His volumes of poetry are bestsellers. Novalis writes to Caroline Schlegel, the beautiful wife of August Schlegel (with whom he is madly in love): "Knight is knight. And we are only his squires." And Brentano, after Ritter's death, to Görres: "Ritter was one of the most wonderful natures ever."

During his years in Jena, Ritter also met Goethe. The latter wrote to his friend Schiller: "Saw Ritter yesterday. He is a true heaven of knowledge." The Weimar privy councillor (something like a minister of the interior) immediately recognized the student's talent. Goethe was working on light at the time. Ritter became his assistant. Goethe is convinced that all things are equal. Since the invisible, long-wave heat radiation infrared had already been discovered, Ritter took up Goethe's idea: "If nature consists of opposing poles, there must necessarily be an equivalent radiation at the opposite end of the color spectrum outside the violet range." But Ritter does not want to speculate, he thinks experimentally. He believes "...that a greater factual investigation is needed to demonstrate polarity in chemistry, magnetism or heat" (Erlanger Literaturzeitung 1801).

First, however, Ritter once again had to struggle with financial problems. He lived free of charge in the garden shed of his friend Hofrat Voigt. He receives worn-out clothes as gifts from friends. He earns a few thalers by selling an occasional series of publications. Several volumes appear: "Beyträge Zur Nähernn Kenntniss Des Galvanismus Und Der Resultate Seiner Untersuchung" or "Physisch-chemische Abhandlungen In Chronologischer Folge", and finally "Das Electrische System der Körper". In his writings, Ritter demonstrates that galvanic processes are always linked to oxidation and reduction.

He was in deep trouble with his client Frommann, he had completely lost the plot. Frommann admonished him several times, but knew that he would never see his money. Ritter could never have survived without the generosity of his friends and acquaintances. Frommann, Goethe, Schlegel, Brentano, Hardenberg - only their generosity kept the young researcher afloat. He could have become a full professor in Jena with a small salary. But he shied away from the formalities of applying and he didn't have the money he would have had to raise to get a professorship.

"Ritter is a true heaven of knowledge"

Goethe

In one respect, Ritter would have had the chance to make a good living. Even before Volta, he had the idea of stacking different metals alternately to form a column. This resulted in a DC battery that was powerful by the standards of the time. He wrote down his thoughts in his diary as early as 1799 - and forgot about them. It was not until 1801, when Volta's battery was already standard, that he came across the notes from that time again and wrote regretfully: "... among the cases that I had already noted down two years ago for experiments to be carried out, I find calculations in which the beginning of a galvanic battery (the added actions) is not the only one. It will always be unforgivable for me to have been so close to it without ever making practical use of what I had in my hands every day."

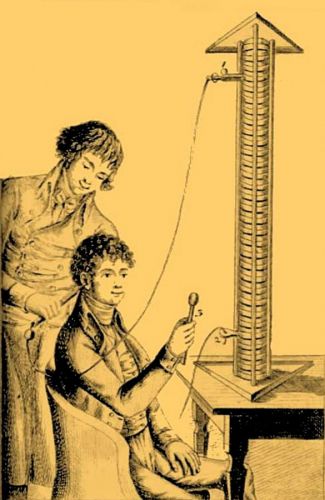

In short: Volta was faster, better organized and networked, and also more skilful. Immediately after his invention, he informed Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society in London, of the battery's weaknesses. In addition, Volta presented his invention in Paris a few days later, which earned him a prize of 6,000 francs from Napoleon himself and the prestigious appointment to the Institut National. Nevertheless, Ritter was able to make Volta's large columns cheaper while maintaining the same performance. The columns consisted of alternately stacked zinc plates and Laubthalers. A Laubthaler was a French silver coin with a diameter of 42 millimetres. Weighing 26 grams, it had a silver content of 90 percent. Dozens, if not hundreds of Laubthaler were needed for an efficient column. Once the battery had been used up, the coins were worthless as a means of payment. Ritter experimented with copper plates and was able to make the column significantly cheaper.

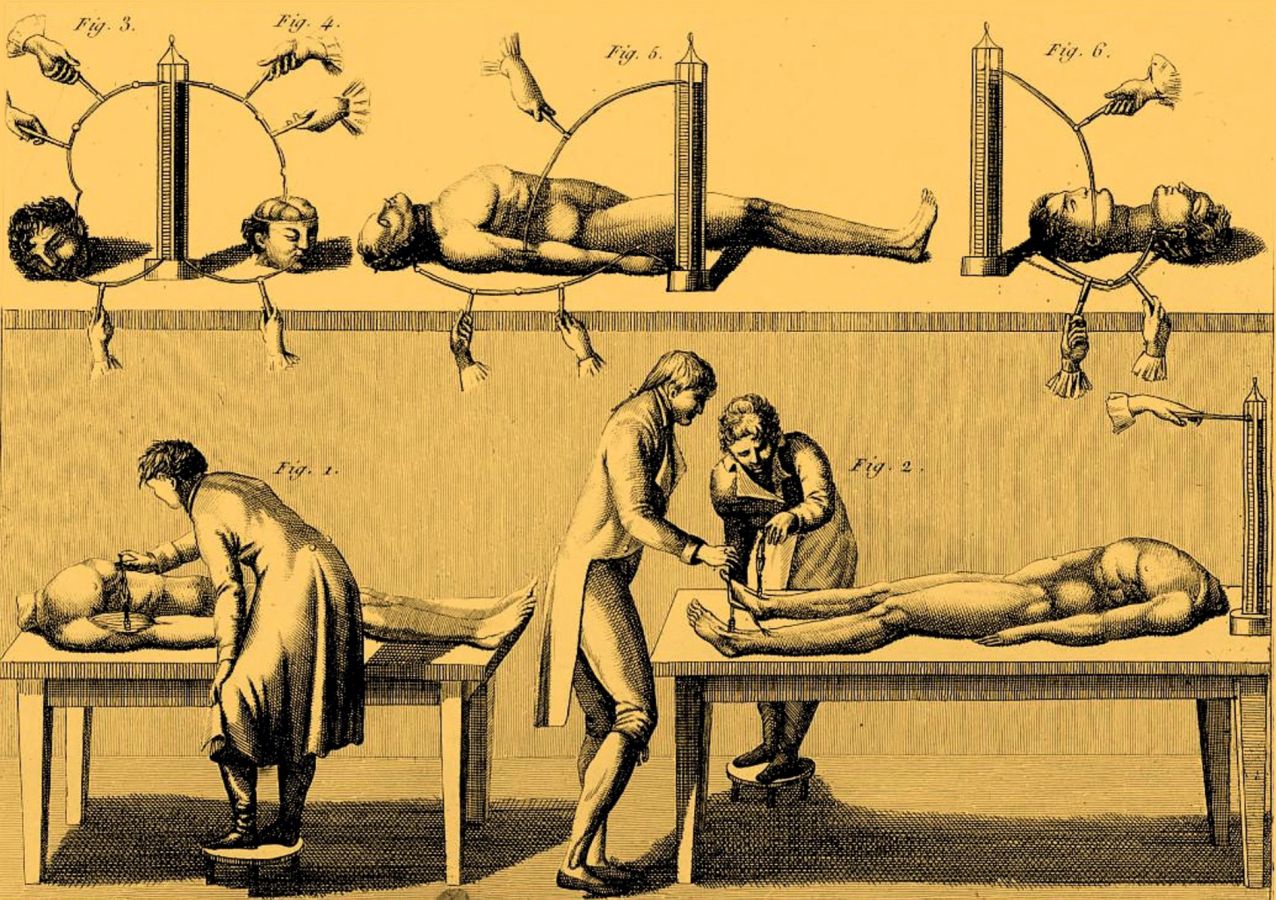

Galvanic laboratories must have been real horror sheds in the Romantic era. Experiments were carried out on amphibians, mammals and, yes, if you could get hold of a human corpse, on that too. Ritter regularly collected amputated limbs from the hospitals in Jena and the surrounding area

Galvanic laboratories must have been real horror sheds in the Romantic era. Experiments were carried out on amphibians, mammals and, yes, if you could get hold of a human corpse, on that too. Ritter regularly collected amputated limbs from the hospitals in Jena and the surrounding area

In this context: There were lively discussions among electroplaters at the time as to whether the columns should end with double end plates (zinc/silver or silver/zinc) or a single end plate (silver/cardboard or zinc/cardboard). The inexplicable fact was that oxygen appeared at the silver end of a column, but hydrogen at the zinc end. Ritter later picked up on this phenomenon. It would become groundbreaking for him in his discovery of the stress series.

Other results that Ritter came up with during his galvanic research included the invention of the dry column and research into the decomposability of water into hydrogen and oxygen. Ritter undertook this research together with his teacher Prof. Voigt. This so-called water electrolysis has not been given much importance to date. Producing hydrogen from fossil fuels is much simpler and more economical. However, in times of climate protection and renewable energies, work is currently underway to use surplus energy from wind and solar power to split water.

"Ritter is a knight. And we are only his squires" Novalis

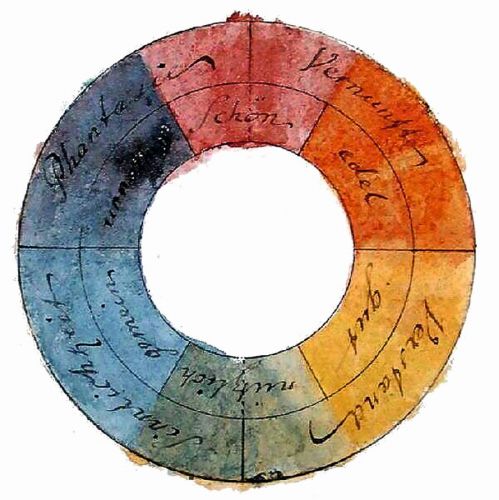

Finally, in 1801, Johann Wilhelm Ritter set about proving the invisible violet light he suspected. The experimental setup is very simple. He cut a strip of paper eight inches long, attached it to a board and coated the paper with horn silver (silver chloride). This light-sensitive substance later became  Goethe's color wheel. The collaboration with the prince of poets inspired Ritter to discover that UV light could also play a role in photography. Ritter then directed white light through a prism, which splits the white light into its components, onto the strip. After a short time, the area of the strip that lies beyond the visible violet turns black - the existence of ultraviolet was thus proven. And thus another possible application of Ritter's proof in modern electroplating technology was found: In modern electroplating plants, components are sterilized and cleaned using UV radiation.

Goethe's color wheel. The collaboration with the prince of poets inspired Ritter to discover that UV light could also play a role in photography. Ritter then directed white light through a prism, which splits the white light into its components, onto the strip. After a short time, the area of the strip that lies beyond the visible violet turns black - the existence of ultraviolet was thus proven. And thus another possible application of Ritter's proof in modern electroplating technology was found: In modern electroplating plants, components are sterilized and cleaned using UV radiation.

In 1804, Ritter married Caroline Münchgesang. A child is on the way, a daughter. His money worries increase. A call from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences came at just the right time. He is to become a salaried member of the academy, along with a teaching position. Ritter's friends put their money together to finance the family's move. Ritter had originally planned to visit his parents and his home town between his work in Jena and his work in Munich. But there was neither enough money nor time.

The family was initially better off in Munich, but the academy soon ran out of money to pay its members. The scientist was in poor health and the first signs of a serious illness appeared. In 1809, his mother died in Samitz. Ritter and his loved ones move to Nuremberg. He died there on January 23, 1810, which his friends thought was due to the many self-experiments Ritter had put his body through. Today it is assumed that the constant worry and deprivation took such a toll on his body and mind that he simply had no resistance to the onset of consumption. His father outlived the brilliant scientist by two years. His wife outlived him by 13 years.

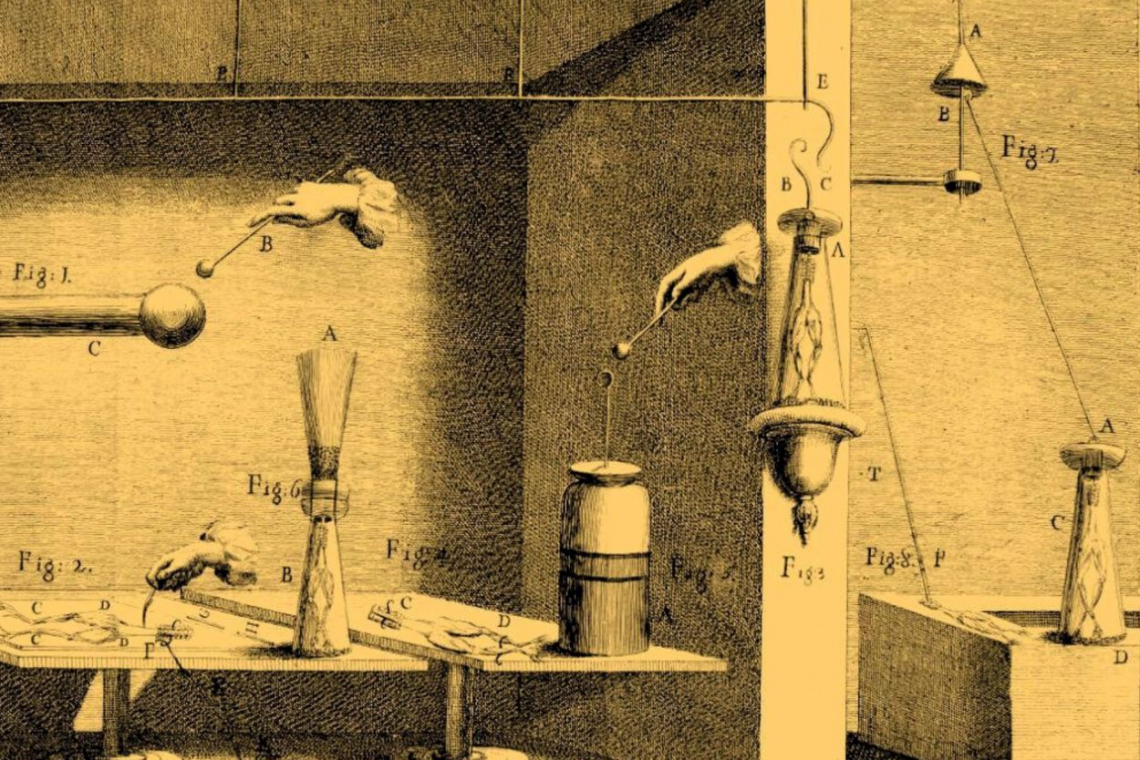

The historical illustrations are from the Frauenzimmer Almanach zum Nutzen und Vergnügen for the year 1803.

- to be continued -