Even the evangelist [1] was probably too late, and Edison's light bulbs don't do justice to the age of this saying. Consequently, we are illustrating the Christmas edition of the 'Seen differently' column with an environmentally friendly LED light. The main attractions of light emitting diodes are the ratio of lumens to watts and their life expectancy.

At 6 to 8 watts, an LED bulb has around 800 lumens of light output and can shine for 50,000 hours. A traditional light bulb consumes 60 watts for this light output and will break after 1200 hours. This means that light-emitting diode lamps can save up to 90 % of the electricity consumption compared to traditional light bulbs with the same brightness.![Abb. 1: Michael Farnes dekoriertes Haus in Hove, England [2]](/images/stories/Redaktion_PLUS/Online-Artikel/thumbnails/thumb_image2_opt.jpg) Fig. 1: Michael Farnes' decorated house in Hove, England [2]

Fig. 1: Michael Farnes' decorated house in Hove, England [2]

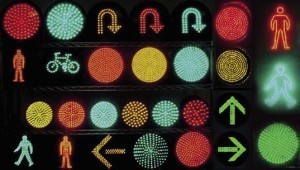

As a result - and this simply has to be critically noted here - both industry and private individuals are using many more of these lamps, which ultimately defeats the idea of saving money. The Christmas fairy lights that are so popular at this time of year are supplied with 200 LEDs instead of the 10 traditional light bulbs used in the past. Mostly questionable taste and exaggerated lighting of homes - not only during the Christmas season - as well as increasingly elaborate illumination of monuments, landmarks and buildings shows that the fear is justified.![Abb. 2: Geschmolzene LED Ampeln nach Protesten in Barcelona [5] Abb. 2: Geschmolzene LED Ampeln nach Protesten in Barcelona [5]](/images/stories/Redaktion_PLUS/Online-Artikel/thumbnails/thumb_image3_opt.jpg) Fig. 2: Melted LED traffic lights after protests in Barcelona [5]

Fig. 2: Melted LED traffic lights after protests in Barcelona [5]

For the electronics industry, this increased use of light sources is of course a profitable development on the one hand. On the other hand, it also poses problems, as the now popular mass production and use of LEDs, especially those used on the surface, presents them with challenges.

According to Forbes [3], the LED market will develop dramatically and reach 70 billion dollars by 2020. These lights are not only used to illuminate homes, but also production halls and warehouses. Ships and naval installations (with their own 'salt' issues) and the aforementioned architectural highlights or activist slogans that then beautify the landscape are also using this highly touted new technology [4].

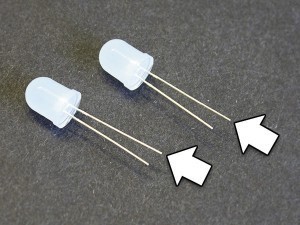

It was realized early on that hand soldering - recommended by LED manufacturers for repairs at best - could not meet the demands of mass production. Applications such as traffic lights required hundreds of wired LEDs and were therefore sent through a surge system - a good example of the learning curve. Fig. 3: LED lamp with heat sink

Fig. 3: LED lamp with heat sink

High failure rates with this soldering method were due to faulty thinking on the part of the application engineers: because they knew that heat was harmful to the lamps, they turned down the preheating and extended the contact time in the surge. However, the connecting wires now directed the heat particularly efficiently from the very hot solder into the interior of the illuminated components, while the infrared preheating was largely reflected by the metal of the wires. Only when the men and women realized that they had to reverse the thought process, i.e. increase the preheating and reduce the contact time in the wave (< 3 seconds), did this lead to success. The failures now approached zero.

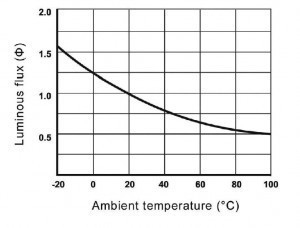

At first glance, the problem does not arise with surface-mounted LEDs, as they do not reach the same temperatures as with wave soldering. But then there is also the heat sink, which is supposed to prevent the lamp from overheating later on - and here too it becomes problematic. At least there is hope that the heavy aluminum heat sinks will soon be smaller, making it easier to reuse the valuable metal when it is disposed of. Fig. 4: Dependence on temperature

Fig. 4: Dependence on temperature

Lamp manufacturers go to great lengths to provide specifications on how their products should be used, although it is noticeable that they allow quite a lot of leeway - usually downwards and less frequently upwards.

A number of parameters must also be taken into account when using LEDs. For example, the ambient temperature and therefore the temperature of the chip directly influences the efficiency and service life of the LEDs. Semiconductor LEDs change their emission properties over time and the intensity of the light output becomes weaker and weaker. The fundamental cause of such ageing is the increase in impurities in the chip (semiconductor crystal).

The synthetic materials used for the housings and lenses (epoxy resin, silicone, etc.) of LEDs also tend to age, which can lead to clouding. In this respect, residues from the soldering process, such as flux vapors, must be taken into account, as cleaning is not easy if chemical reactions are not to be accepted. Fig. 5: Wired LEDs

Fig. 5: Wired LEDs

Like most electronic devices, LEDs work well until external influences impair their performance. Such influences can include the electrostatic attraction of dust, humid or corrosive environments, chemical or gaseous contaminants and many other possibilities. It is therefore extremely important that the end-use environment is considered in detail to ensure that the correct products can be selected.

Transparency and color shift must therefore be considered when coatings are to be used against negative environmental influences. Quite extensive studies have also been carried out on this subject and it seems that acrylic chemistry has been chosen, but silicone-based and polyurethane coatings are also used, which are advantageous for certain purposes.

Damage caused by condensation from air humidity, UV stability and salt spray protection must be verified using the appropriate test procedures. Attention is also paid to the printed circuit board itself, as it is precisely these influences that rank high on the list of situations that also contribute to its failure. Fig. 6: LED traffic lights

Fig. 6: LED traffic lights

The lacquers are applied by dipping or spraying. The thickness is then between 25 and 75 µm, with thicker polyurethane coatings (up to 8 mm), for example, being more prone to color shift.

In addition to the criticism regarding the effects of more and more lighting on fauna and flora, disposal is also not entirely straightforward. Although LED lamps do not contain mercury, they should not simply be thrown in the garbage can when they are no longer needed.

Literature and notes:

Seong - Rin Lim et al: Potential Environmental Impacts of Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs):

Metallic Resources, Toxicity, and Hazardous Waste Classification, Environ. Sci. Technol., 2011

Emma L . Stone et al: Conserving Energy at a Cost to Biodiversity? Impacts of LED Lighting on Bats, Global Change Biology, 2012

Amit Patel et al: Quantifying Qualitative Attributes of Cored Solder Wire in LED Luminaire Soldering - Part I, Proceedings of SMTA International, 2015

Knightbright, Application Notes for Through-Hole LEDs

Cree High-Brightness LED Soldering & Handling, CLD-CTAP001 Rev 22

Piyush Baksh:; The environmental benefits of LED lighting, January 30, 2015

References:

- A widespread metaphor: The Greek philosopher Parmenides (c. 515 BCE) already depicts the act of knowledge as a journey from night into day; in the Bible we read: "the light must always dawn on the righteous" (Matthew 4:16)

- Image: David McHugh/Brighton Pictures

- https://www.forbes.com/forbes-media/

- First LED by Russian inventor Oleg Losev (1903 -1942) in 1927

- Catalan independence supporters set fire to the country (17.10.2019)