After threshing with the flail, you waited for a good wind to separate the wheat from the chaff. The lighter husks were carried further away by the breeze than the grains, which landed close to the cloths. This was dirty and hard work, which is of course now done by machines, at least in most areas. Nevertheless, this work process, which was still common in the countryside after the Great War, can currently be shown to children in some museum villages. Similar activities have been adopted in poorer countries for the recycling of electronic products that have reached their end of life for 'inexplicable reasons'. In fact, people are also trying to make this work easier with machines.

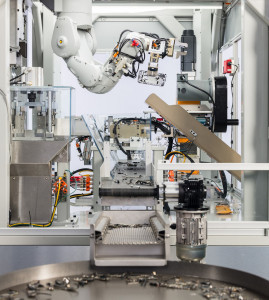

In 2016, for example, Apple unveiled the robot 'Liam', which can disassemble one of its phones in eleven seconds, to much fanfare and amazement. Thanks to 'Liam', around 1.2 million of these coveted products can be turned into potentially usable scrap every year. If Apple makes a few more of these available, it may be possible to deal with the pile of 231 million new cell phones without exploiting the poorest people in various developing countries.

'Daisy', as a lone fighter of planned obsolescence, quickly dismantles cell phones that have already been designed as unrepairable'Liam', who returned shortly afterwards in 2018 under the name 'Daisy', is probably intended to conceal the fact that these cell phones are already designed as unrepairable. After all, the central problem not only in this technology sector is a strategy geared towards profit. Planned obsolescence ensures that the customer always has to buy a new one and thus secures the company's future profits. In addition, there are always small, carefully psychologically planned improvements that are offered in quick succession.

'Daisy', as a lone fighter of planned obsolescence, quickly dismantles cell phones that have already been designed as unrepairable'Liam', who returned shortly afterwards in 2018 under the name 'Daisy', is probably intended to conceal the fact that these cell phones are already designed as unrepairable. After all, the central problem not only in this technology sector is a strategy geared towards profit. Planned obsolescence ensures that the customer always has to buy a new one and thus secures the company's future profits. In addition, there are always small, carefully psychologically planned improvements that are offered in quick succession.

Vance Packard [2] had already denounced some of these methods. Since then, the world has not become any less greedy, as the figures for 2022 show: Dear customers currently own around 16 billion cell phones worldwide and are estimated to have thrown away (we like to say 'disposed of') more than 5 billion of them or entrusted them to various drawers.

Durability - and what used to be called 'good quality' - has a direct impact on sales. This is because the fewer repeat purchases are made, the lower the company's production will be. If used products are offered - via the internet, for example - some potential customers may be more inclined to save some money than to buy the latest version of this magic weapon. Hence the propaganda that psychologically forces elementary school children not only to wear the latest clothes with advertising stickers but also to proudly show off the very latest electronic device in class.

Precious metals on the scrap heap

Even 'Liam' and 'Daisy' will probably add to the pile of electronic waste at the end of their years of service, as cell phones only make up a small part of the huge mountain that is piled up here. Worldwide, 44.48 million tons are expected. The vast majority of these are not recycled, even though they are full of expensive materials. After all, neither the circuit board nor the component can do without gold, copper, silver, palladium or rare earths. One ton of e-waste from computers and laptops contains around 70 kg of copper, 140 g of silver and 30 g of gold - a ton of cell phone scrap, on the other hand, contains around 240 g of gold, two and a half kg of silver, 92 g of palladium, 92 kg of copper and 38 kg of cobalt.

However, the regions of the world provide very different scenarios. Estimates range from Europe, where 50-55% of e-waste is collected or recycled, to other and especially low-income countries where 95% and sometimes even over 99% ends up in landfills, the environment or even the sea.

From a rational point of view, it makes more sense to extract these raw materials from scrap than to rob them from nature. After all, it is estimated that it costs seven times as much to mine such resources as it does to recover them from electronic waste. Discarded cell phones (please remove batteries by force beforehand, as they are attached with industrial adhesives!) provide significantly more of the precious elements than natural ores.

Both this aspect and the potential danger to workers (Greenpeace reported in 2008 that measurements in the air and soil at the waste dump in Ghana were 50 times higher than the values considered harmless to health) were soon recognized. The 'Basel Convention'[3] on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal of March 22, 1989 can serve as a benchmark.

Burning a circuit board over an open fire - the dioxins and furans released pose a health riskSomecountries have also reacted themselves and are reluctant or no longer willing to take their waste from the West, meaning that these exports have to be redirected. China started to reduce imports of scrap at the end of 2017. This can also be interpreted indirectly as a reaction to American trade restrictions, as this has made life much more complicated for some cities in the USA. Instead of sorting the waste and recycling it, they cart it straight to the landfill, much to the regret of environmentally conscious people. Franklin (New Hampshire) abandoned its successful 'recycling' program when the cost per ton climbed from about $6 to $125 per ton - and that's just one example of numerous other places in the US. Relevant studies show that 50-80% of e-waste is shipped overseas and an additional 2 million tons per year ends up in US landfills.

Burning a circuit board over an open fire - the dioxins and furans released pose a health riskSomecountries have also reacted themselves and are reluctant or no longer willing to take their waste from the West, meaning that these exports have to be redirected. China started to reduce imports of scrap at the end of 2017. This can also be interpreted indirectly as a reaction to American trade restrictions, as this has made life much more complicated for some cities in the USA. Instead of sorting the waste and recycling it, they cart it straight to the landfill, much to the regret of environmentally conscious people. Franklin (New Hampshire) abandoned its successful 'recycling' program when the cost per ton climbed from about $6 to $125 per ton - and that's just one example of numerous other places in the US. Relevant studies show that 50-80% of e-waste is shipped overseas and an additional 2 million tons per year ends up in US landfills.

Once all the rage, now dumped as e-waste in drawer cemeteries: cell phones and smartphones from the day before yesterdayHowever, Europe should not pat itself on the back too much either, as the so-called CWIT study ('Countering WEEE Illegal Trade'), which was commissioned by the EU, is not exactly flattering in its findings [4]. The illegal disposal of electronic waste alone raises eyebrows. Instead of separating the wheat from the chaff when it comes to electronics, this could possibly tempt at least some politicians to think about where the cause can be found: in the companies.

Once all the rage, now dumped as e-waste in drawer cemeteries: cell phones and smartphones from the day before yesterdayHowever, Europe should not pat itself on the back too much either, as the so-called CWIT study ('Countering WEEE Illegal Trade'), which was commissioned by the EU, is not exactly flattering in its findings [4]. The illegal disposal of electronic waste alone raises eyebrows. Instead of separating the wheat from the chaff when it comes to electronics, this could possibly tempt at least some politicians to think about where the cause can be found: in the companies.

About the person

Prof. Rahn is a globally active consultant in the field of connection technology. His book on 'Special Reflow Processes' was published by Leuze Verlag. He can be contacted at

References

[1] From the Luther Bible: Luke 3:12: '... he will separate the wheat from the chaff ...'

[2] Vance Packard (1914-1996) was an American journalist, social critic and bestselling author.

[3] www.bmuv.de/gesetz/basler-uebereinkommen-ueber-die-kontrolle-der-grenzueberschreitenden-verbringung-gefaehrlicher-abfaelle-und-ihrer-entsorgung (accessed 21.03.2023)

[4] www.weee-forum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/CWIT-Summary-Report_Final_Medium-resolution.pdf (accessed 21.03.2023)