Occupational health and safety are important issues of our time. It wasn't always like this. Around a hundred years ago, you had a safe workplace if you survived the week.

The reference book "Galvanotechnik" by W. Pfanhauser (1941) begins with the words: "Work as if you had a hundred years to live, and work as if you had to die tomorrow."

The fact that the topic of work-life balance was not yet so fashionable at the time can be seen on the following page: "I feel the need to express my sincere gratitude to my employees, who have devoted their free time to this work with the greatest diligence and conscientiousness during many months of strenuous professional work."

This refers to the fact that the employees had to slave away for well over eight hours a day so that Mr. Pfanhauser could complete the book.

The years before and after were no better. A good indicator of the changing times is vacation and the associated arrangements. From the end of 1945, most West German states had a right to at least two weeks' annual leave, and from 1963, all employees nationwide were even entitled to three weeks. A great achievement that comes with obligations. Vacation is supposed to be relaxation for body and soul. How this should look in detail is usually determined by life partners, relatives, friends or neighbors.

But three or more weeks are of little help if your daily work is full of dangers. In the above-mentioned textbook, it was still considered necessary to point out that electroplating shops should not be set up in dark, poorly ventilated cellars. The conditions that still prevailed 15 years later can be seen in the following questions and answers, as they were posed in the magazine "Galvanotechnik" in 1956.

Health protection

Question: 1. is there a legal obligation to provide electrolytic degreasing baths with an extraction system?

2 I have been plating for a long time. After 14 days I developed insomnia and nosebleeds. It is a brass ring bath 1800 ltr. 30-35 °C, 3.5-4 V, 200 A. The doctor diagnosed nerve damage in a colleague at work. I now claim that these illnesses are due to the strong gas development of the brass bath. Am I right?

Answer: Question 1: There is no legal obligation to equip electrolytic degreasing baths with a suction device. The spray mist generated during the operation of these baths, which often causes nuisance to employees, can be easily removed by using degreasing baths containing wetting agents, which form a cream-like foam on the bath surface that retains the fine spray mist.

Question 2: Whether the symptoms of illness mentioned are due to the allegedly strong gas development of the brass bath cannot be assessed with certainty by laypersons. In addition, reference is made to the accident prevention regulation "Electrolytic and chemical surface treatment of metals". Available from the Federation of Institutions for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention, Central Office for Accident Prevention, Bonn.

Source: Trade magazine "Galvanotechnik" 1/1956

When the author of these lines began his training, a few decades had already passed. In the 1990s, the Love Parade, Mayday, raves and the Internet were topics in the workplace. A lot had changed in terms of occupational health and safety. There were extraction systems, safety clothing, safety goggles and information about how toxic cyanide and nitrous gases are. This was not a matter of course in a large company, but in many smaller contract electroplating plants. But even the large company could cause many an insensitive and negligent blunder.

About a year before I started my apprenticeship, there was a fatal accident at a hot bluing line. An employee tipped in a bag of bluing salt in one fell swoop, the reaction was immediate and even years later the traces could be seen on the five-meter-high ceiling. The fact that the death notice was printed in the daily newspaper at the same time as the job advertisement can be dismissed as bad timing. Not much was really learned from the incident. The bluing was cleaned once a year. To do this, the alcoholics were given schnapps until they were ready to do the job. Incidentally, the most common cause of death in the department was cirrhosis of the liver.

There were various reasons for the questionable conditions in the factories at the time. In part, this was due to ignorance or underestimation of the dangers. Working with chromium (VI) compounds is still normal in many companies today, as is working with cyanides. In the past, numerous no less dangerous chemicals and elements were added. Mercury, cadmium, lead, chlorinated hydrocarbons (tri, per, methylene chloride) for parts cleaning, to name but a few. In the mid-1990s, an employee of a large grinding shop reported long-lasting withdrawal symptoms among his colleagues after the cleaning process was converted into a closed system.

In the worst case, a process in an electroplating shop even achieved a triple of sins:

-

It was harmful to employees.

-

The coating produced was harmful to customers and the environment.

-

The waste products produced in the electroplating shop were not or only insufficiently detoxified/disposed of.

The carelessness of earlier days can be seen in the technical literature. Readers there liked to ask questions that would be more difficult to justify today. Here is an example from Galvanotechnik 1/1969, page 33:

"Can uranium be electrolytically annealed? Can you give us more technical details?"

The answer was surprisingly sober and competent, but is not the subject of this article.

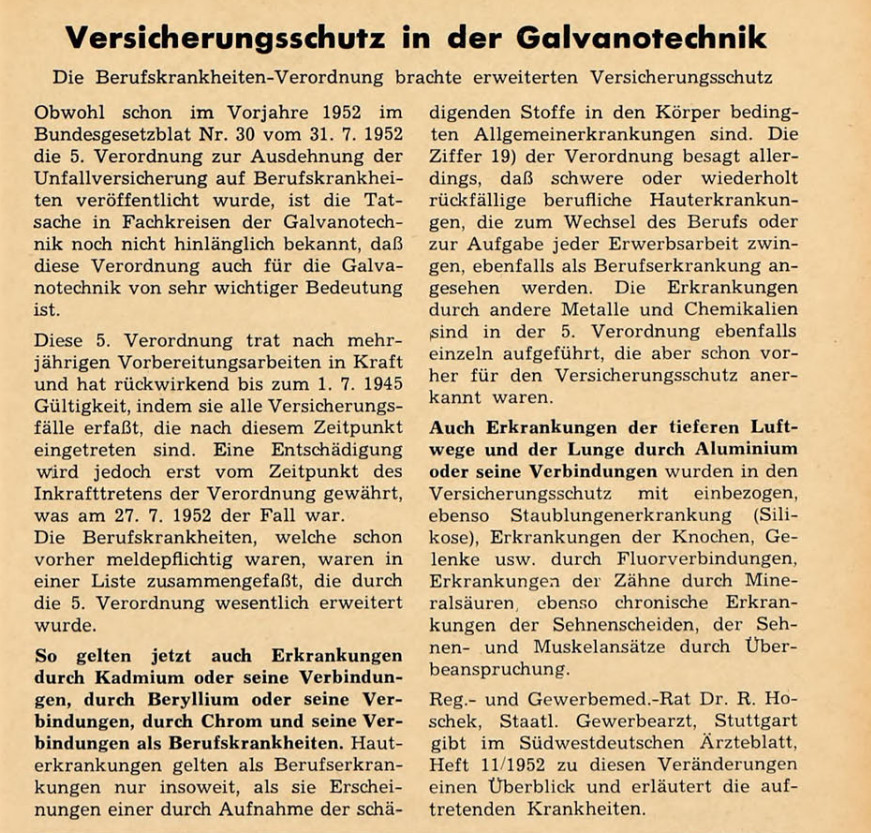

Even if, from today's perspective, many questions and answers seem careless and clueless, there were certainly efforts to improve the situation. An excerpt from GT 11/12-1953 on the subject of insurance cover serves as an example:

The legal situation and insurance cover are one thing, but it takes a long time for dangers and their effects to penetrate the consciousness of employees and superiors. The author recalls his first technician job almost exactly 20 years ago. The owner of a small electroplating company tried to cut corners, mainly to invest the money saved in his own villa and expensive cars. Anyone who wanted new rubber gloves had to present the old ones to the boss, who decided whether the holes were big enough to justify new gloves.

One day there was an inspection by the employers' liability insurance association. This revealed numerous deficiencies, particularly in the area of occupational safety. The dialog between the BG and the boss went something like this:

BG: "Safety goggles are missing here."

Boss: "Costs money."

BG: "And gloves are missing here."

Boss: "Also costs money."

BG: "We need a fire extinguisher here."

Boss: "Too expensive."

BG: "An eyewash is missing here."

Boss: "It's also too expensive."

BG: "What is the health of your employees worth to you?"

Boss: "Not a penny!"

The statement and the conditions in the company had no consequences. Even years later, the boss boasted that he had heard nothing more from the BG. The same applied to the failure to carry out wastewater inspections, which prompted the boss to allow some of his zinc-nickel wastewater to enter the sewer system untreated. That was 2010, not 1910.

Despite all the achievements, sad conditions still prevail in some companies today, albeit perhaps at a slightly higher level. The author remembers a CEO of a large electroplating company in Switzerland refusing to purchase a defibrillator in accordance with regulations on the grounds that his employees were all "young, sporty and healthy". He dismissed the objection that this was an outright lie by saying that in an emergency they could go to the neighboring company 50 meters away. They have a defibrillator, you just have to ask if you can borrow it.

The idea that occupational safety, health protection and environmental protection "only cost money" is still deeply rooted in the minds of responsible people today, even though this has long been disproved. The example of the defibrillator is staggering when you consider that the company was turning over millions a year but was not prepared to invest CHF 3,000 to save the lives of employees in an emergency.

But alongside the black sheep, there are also some great companies that place great value on protecting their employees. It pays off in the long term. This is not only noticeable in fewer sick days and thus downtime, but also in motivation. A safe workplace is much more motivating than an unsafe one that makes you ill. It is motivating when you know that you will be helped if the worst comes to the worst and that you will be seen as a person. In addition to motivation, trust and security create identification with the workplace, the company and the people involved. Finally, a negative example from the above-mentioned company with the employers' liability insurance association:

An older employee had a heart attack at the rack system. The boss was informed and he immediately drove the employee to hospital. He survived, but had to be operated on. The rehab took some time. After eight weeks, the employee was still on sick leave. The boss went berserk when he saw his employee on his bike in town. His opinion: if you can ride a bike, you can work. At work, the boss got carried away and said: "How ungrateful can you be? I also had a heart attack once, but it was much worse and I was back at work after just two weeks. I could have let him die at the plant! But I drove him to hospital, saved his life and now he's happily going for a bike ride at my expense!"

Naturally, this reaction did not go down well. This and numerous other incidents led to all employees who saw better opportunities for themselves gradually leaving the company. The rest just worked to rule. A few years later, part of the electroplating shop burned down due to a lack of sensors and maintenance work - the boss himself suffered his second heart attack a month later, from which he died.