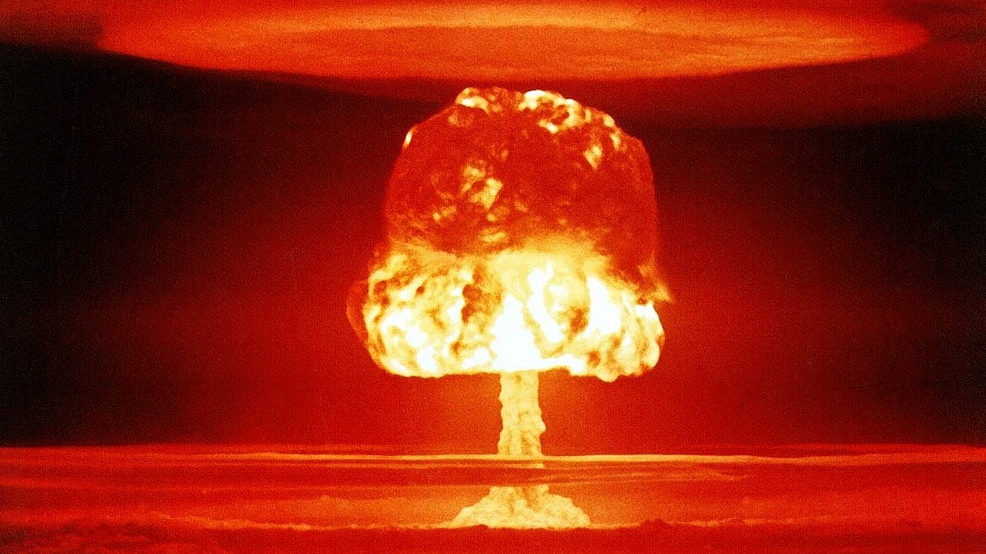

A three-hour film about a physicist named Julius Robert Oppenheimer is currently showing in cinemas, and the media hype can only be surprising. "Oppenheimer" - as the film is titled - is hardly about physics, although it is about the first construction of an atomic bomb and its use in the Second World War. Instead, the moving images provide a detailed view - alongside gigantic explosions and walls of fire - of American politicians who, like a modern Prometheus, want to punish and wear down Oppenheimer after he has stolen the nuclear fire for them, as in Greek mythology.

The hunt for Oppenheimer began when he said that a more powerful hydrogen bomb was not needed after the atomic bomb, especially not after first the Germans and then the Japanese had capitulated as the USA's opponents in the war. Oppenheimer tried to explain his moral concerns in a conversation with the American President Harry S. Truman, but the physicist only earned contempt from the politician, who had given the order to drop two bombs and was surprised that Oppenheimer had been working on a weapon for years in the hope that he would not have to use it. With the words "I don't want to see that crybaby here anymore", Oppenheimer was dismissed from the White House, and so the most famous man at the end of the Second World War, celebrated on the front pages of magazines, was simply dumped. In the movie theater, we watch in bewilderment at the dismantling of the scholar who had previously been chosen to save the nation. But how could the hero of the movie, who himself believed he couldn't even run a snack bar, lead the Manhattan Project to success? After all, 40,000 men had to work in coordination in the desert and a budget of billions of US dollars had to be managed. I think I can give two answers to Oppenheimer's management of the Manhattan Project. Firstly, there was the fear that the Jew Oppenheimer had of the Nazis, and it shocked him to imagine that Hitler had such a thing ready for use in his suitcase before it was available to the Allies. The second answer to Oppenheimer's success lies in his universal erudition, which on the one hand everyone admired and on the other allowed every specialist to work for his own personal glory - a win-win situation during the war.