Empa researchers have succeeded in extracting large quantities of the pigment melanin from fungi. The gigantic Hallimasch fungus in the service of science is one of the largest living organisms in the world. The applications of this "black gold" range from surface technology and wood preservatives to the construction of musical instruments and water filters.

Its properties are astounding and its applications correspondingly diverse: the pigment melanin, which protects human skin from damaging UV rays (and gives us a summer tan), is a veritable treasure trove for new materials and technologies. Although this miracle substance is found in nature, the complex biopolymer has so far only been able to be produced artificially on an industrial scale using expensive and complex processes in which not all properties can be reproduced. Processes to obtain natural melanin from microorganisms have also shown a low yield to date. It is therefore not surprising that the substance is many times more expensive than gold. Researchers at Empa have now succeeded in getting fungi to produce the "black gold" in a simple and highly scalable process. "Melanin is extremely stable against environmental influences and is not only interesting as a pigment, but also far beyond that for the development of innovative composite materials," says Empa researcher Francis Schwarze from the "Cellulose & Wood Materials" department.

In their search for simpler, cheaper processes for the production of natural melanin in large quantities, Schwarze and his team came across a fungus that is actually found as a pest in forests: Armillaria cepistipes, the onion-footed honey fungus. Its amazing metabolism binds heavy metals, makes wood glow in the dark - and produces melanin. And in large quantities. "We have selected a promising line of the hallimash fungus that now produces around 1000 times as much melanin with our technology as other microorganisms with which pigment production has already been attempted," says Schwarze.

The trick: the selected fungal strain lives in a nutrient fluid and releases the melanin into the environment. "This system now enables sustainable production that no longer requires complex extraction steps like previous microbiological procedures," explains Empa researcher Javier Ribera, who is heavily involved in the process. After three months, one liter of hallimash culture has already produced around 20 grams of melanin.

The facilitated and sustainable production of melanin now enables Empa researchers to drive forward projects for the development of innovative materials. These include, for example, a system for water purification: As melanin is able to bind heavy metals, it can be used to develop new types of water filters. "We have integrated the organic melanin into artificial polymers such as polyurethane," explains Empa researcher Anh Tran-Ly. Using electrospinning, the polymer mixture was spun into the finest fibers to form membranes Up to 94% lead can be removed from contaminated water using the melanin-based composite membranes, the Empa team found out.

As black as ebony

In nature, fungi use melanin pigmentation, among other things, to protect themselves from competing organisms that invade from the environment. With a new technology, the coloring substance can now also be used to protect much larger communities from human influence: Melanin can be used to conserve tropical forests where the valuable ebony grows.

Tropical ebony is also considered particularly valuable because of its unique dark color. A sustainable process that enhances ordinary native spruce wood into a product that is just as visually attractive allows vulnerable tropical forests to breathe a sigh of relief. "When spruce wood is placed in a melanin suspension, a deep dark wood can be produced that is comparable in color to ebony," says Empa researcher Tine Kalac.

Helpful trick from the mushroom box

In order for the black coloring to penetrate the wood better, the researchers resorted to another trick from their mushroom box: The watery porling, Physisporinus vitreus, is the causative agent of white rot and is also a wood pest. It grows like a sponge on trees and decomposes the supporting lignin in the wood.

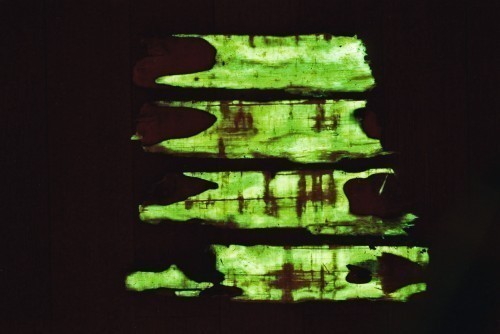

Wood infested by the white rot pathogen, Physisporinus vitreus.

Wood infested by the white rot pathogen, Physisporinus vitreus.

Using a process specially developed at Empa, the wood is now treated with the white rot fungus for just long enough for the melanin suspension to penetrate deep into the wood structures while the wood remains stable.

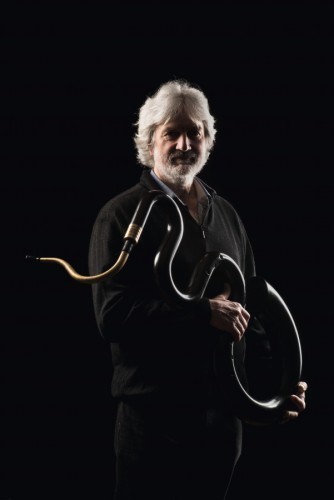

Serpentino - The little snake among the instruments

As the hallimash fungus uses melanin as a weapon against its fellow species, it makes sense to use this move to protect wood from harmful fungi. In order to develop melanin-based wood protection, Empa researchers are involved in a recently launched interdisciplinary research project supported by Innosuisse, the Swiss Innovation Agency. They want to recreate a historical wind instrument, the serpentino (small snake).

INFO

Gigantic honey fungus

It is called the honey fungus or hallimash and is one of the most amazing creatures on earth. It may sprout inconspicuously on the forest floor in the classic mushroom shape, adorned only with a decorative strip around the style, like a bracelet, which gives it the Latin name "Armillaria".

Much more impressive, however, is its web of black strands that it draws across the wood and ground. Fungal threads, surrounded by a black melanin-containing protective layer, join together to form meter-long thick bundles and search for new habitats and food sources. These so-called rhizomorphs can also penetrate tree roots as parasites, climb up the trunk and decompose their host from the inside.

With a size of several square kilometers, the largest living organism in the world, an approximately 2400-year-old Hallimasch network, extends in the US state of Oregon. In Switzerland, the largest mushroom in Europe can be found on the Ofen Pass. This Hallimasch covers an area the size of 50 football pitches. It also owes its age of around 1000 years to the pigment melanin, which protects the black fungal threads from environmental damage.

Harmful microclimate in the instrument

In addition to the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland and the Basel Historical Museum, SBerger Serpents in Le Bois (JU) is the partner responsible for the practical implementation of the project. Company founder Stephan Berger is enthusiastic about the rebirth of the rare instrument: "The serpentino was used over 400 years ago and was the inspiration for modern instruments such as the saxophone," he explains. Although it is a challenge for musicians to master the instrument, the sound is incomparable, Berger enthuses. "The serpentino produces sounds that are rich in overtones and very touching." Originally, the wind instrument was used in churches to support the singing, as it covers the registers of the human voice and can therefore "support" a choir, explains the passionate instrument maker.

Although today a trend towards historically informed performance practice means that the serpentino is in demand, Berger is unable to supply his customers with instruments: The peculiarly curved original instruments have become rare. This is because the interior of the walnut snake not only produces an incomparable sound - there is also a war raging: the condensation from the musicians' breath creates a humid microclimate that provides excellent conditions for the growth of all kinds of pests. And so microbes and fungi decompose the centuries-old instruments and gradually destroy the last original specimens.

The research project's faithful serpentino replicas are to be sustainably protected from this damage. This is where the Empa researchers' melanin comes into play: "If we can use a melanin-based wood protection impregnation, not only the newly built serpentinos can be saved from decay," says Berger. Other woodwind instruments that are currently built with indigenous, less resistant woods could also benefit from such a protective coating. The collaboration with the Empa team is therefore exciting for instrument making in two respects.

INFO

Melanin: Pigment against environmental stress

"Melanin" is a generic term for a large group of coloring substances. The pigment melanin gives our hair, eyes and skin their color.

It is found in bird feathers, sheep's wool and in the ink of squid. Plants, fungi and even bacteria also have this miracle substance.

Its job is to protect the organism from environmental stress. The darkening of the skin when exposed to sunlight is one example of this.

In turn, melanin gives fungi an even more amazing ability: thanks to melanin, they can even use radioactivity to generate energy in their own metabolism.